Click here for a key to the symbols used. An explanation of acronyms may be found at the bottom of the page.

Routing

Routing Post 1964 Signage History

Post 1964 Signage History▸In 1981, Chapter 292 defined this route by transfer from Route 24: "Route 17 in Oakland to Route 580."

▸In 1986, Chapter 928 changed "Route 17" to "Route 880"

▸In 1988, Chapter 106 clarified the routing: "Route 880 in

Oakland to Route 580 in Oakland".

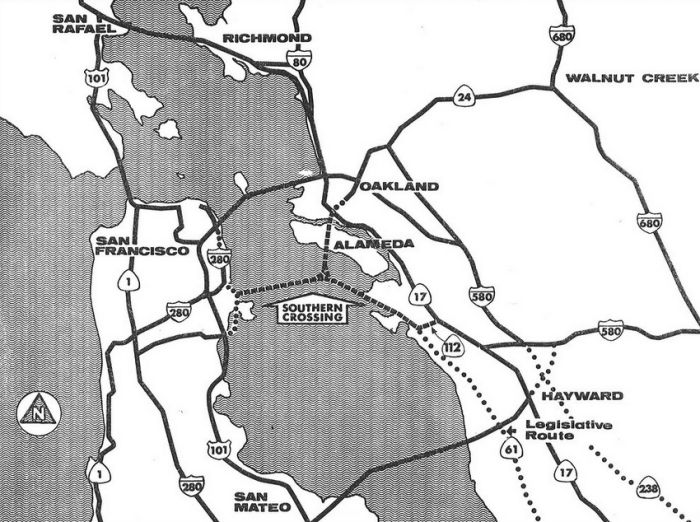

Chris Sampang indicated that this might have originally been a possible

connector to the Southern Crossing. This is confirmed by the map to the

right (click on the map for a larger image). The map, from The

Southern Crossing: A Brief Report (more photos on the photostream) shows Route 980 continuing south to connect with the

I-280/I-380 Southern Crossing. See the page on I-380 for details on the

Southern Crossing

Chris Sampang indicated that this might have originally been a possible

connector to the Southern Crossing. This is confirmed by the map to the

right (click on the map for a larger image). The map, from The

Southern Crossing: A Brief Report (more photos on the photostream) shows Route 980 continuing south to connect with the

I-280/I-380 Southern Crossing. See the page on I-380 for details on the

Southern Crossing

Pre 1964 Signage History

Pre 1964 Signage HistoryThis route was LRN 226, defined in 1959, and was signed as part of Route 24 between 1964 and 1984.

There are two aspects to the freeway: The connection through Oakland proper (between I-580 and I-880), and the potential connection to a bridge connecting the East Bay to San Francisco.

With respect to the bridge aspects, the impetus for the freeway first emerged in 1927, when engineers identified a number of routes for a possible bridge connecting the East Bay to San Francisco, according to Connect Oakland, a group that formed in 2014 to advocate for the freeway’s removal. Although planners ultimately chose the current alignment, which knits West Oakland to Yerba Buena Island and San Francisco, planners began considering a second crossing almost as soon as the Bay Bridge opened. By 1948, municipal leaders were mulling a second transbay crossing connecting Castro and Grove streets in Oakland with Army Street in San Francisco. The idea was to build a connection from the Grove-Shafter Freeway, known today as Route 24, with a new bridge. That bridge never materialized.

As for the crossing in Oakland: there is a connection to a historic use

of freeways to divide and segregate communities. The Federal Housing

Administration, created in 1934, insured mortgages covering eighty percent

of the cost of a house — but only in all-white neighborhoods. They

judged as risky -- and used a practice known as red-lining -- for

properties in racially mixed neighborhoods or even in white neighborhoods

near black ones that might possibly integrate in the future. An FHA

underwriting manual notes that highways were “effective in

protecting a neighborhood and the locations within it from …

inharmonious racial groups.” Miami, Los Angeles, and other big

cities routed freeways to cordon off, or pave over, minority

neighborhoods. The double-decker Cypress Freeway plowed through the middle

of West Oakland in the 1950s, and another freeway was planned (but not

constructed) that would mark a firm line between white Oakland, and black

West Oakland — I-980. But by the time construction started in the

1960s, things were starting to change. The Civil Rights Movement was

gaining traction, the courts were ruling that segregation could no longer

be government policy, and the Black Panther Party was rising up in West

Oakland. The freeway would no longer divide white and black residents

because black people had already moved into the rest of Oakland at that

point. Construction started in 1962, and soon bulldozers began clearing a

path through Oakland. Demolition crews knocked down houses, setting off

protests, but there wasn’t much activists could do. However, in

1972, a young lawyer named Stephen Berzon, funded by President

Johnson’s Legal Services Program, came up with an idea for a

lawsuit. It wasn’t enough to relocate people, he argued; the

California Department of Transportation also needed to replace the housing

it tore down. A federal judge agreed with Berzon and gave him the

injunction he sought, stopping the earth movers. The project sat in limbo

for years, with the construction site acting as a parking lot for heavy

equipment. People from the neighborhood told Berzon they didn’t

necessarily want to stop the freeway, they just wanted decent homes. A

freeway would be better than what the earth movers left behind. In

1973, Roger Clay Jr., a young attorney living in West Oakland, began

working with Berzon. Berzon worked to make sure that the government built

new housing and honored the city’s promises to keep his

clients’ rents low. This led to the community shaping the design of

the freeway, and is why the freeway was constructed as an depressed

roadway instead of elevated. That way, it wouldn’t form as much of a

barrier and so that the earthen sidewalls would contain some of the noise

and pollution. It is also why the first two miles are elevated (pre-1972

construction), and the end is elevated (to connect with I-880).

(Source: SF Streetsblog, 4/17/2019)

In the end, Oakland removed 503 homes, 22 businesses, four churches and

155 trees to make way for a speedier connection to downtown.

(Source: Connect Oakland)

Status

StatusRemoval of I-980

In November 2015, a community movement surfaces that

wants to remove I-980. The argument is that I-980 is the lowest traffic

segment of urban freeway in Oakland, and the most valuable land (whether

from a community or commercial perspective) taken up by a freeway.

Removing it will reunite historic West and downtown Oakland. The cause is

being chapioned by "Connect Oakland" and John King, the urban design

critic of the SF Chronicle. According to King, the plan would replace the

freeway with "a boulevard lined with housing at all price levels,

reknitting the urban landscape." The proposal could also "include space

for BART beneath the boulevard, a tunnel that could connect to a second

BART tube from Oakland to San Francisco." King describes Octavia Boulevard

in San Francisco, for example, as a comparable example for the future

direction of Connect Oakland. The proposal has been pressed "for the past

year by a handful of local architects and planners with good intentions

but little clout," reports King, but city recently moved the idea into a

new level of legitimacy when it requested "requested $5.2 million from the

Alameda County Transportation Authority to begin planning studies of an

I-980 conversion and a second BART tube."

(Sources: Planetzen, 11/17/2015; Neighborland; SF Chronicle, 11/14/2015 (paywalled))

In January 2017, it was reported that the Congress for

the New Urbanism had released a report highlighting I-980 on its

“top 10” list of urban freeways across the country that they

say serve as a blight to the communities they bisect. The call echoes

those of local advocacy groups, as well as the city of Oakland, which is

studying the freeway’s conversion to a boulevard as part of its

$2.35 million downtown specific plan. The plan will create guidelines for

future development in the heart of the city. Completed in 1985, the

roughly two-mile stretch of freeway runs from its intersection with

Interstate 880 near Jack London Square to its nexus with Highway 24 near

the I-580 interchange, blanketing more than 40 city blocks. As in many

communities across the country, the construction of urban freeways

devastated West Oakland, severing neighborhoods, isolating communities and

plunging the neighborhood into several decades of decline. But some social

justice advocates have mixed views about whether removing the freeway now

would heal the economic wounds of decades past. As of 2017, the highway is

underutilized, reaching only 41.9 percent capacity at its peak, with

average levels much lower, according to a UC Berkeley study of the

corridor. Connect Oakland, along with the city of Oakland, proposes

removing the freeway to its intersection with Grand Avenue, where traffic

volumes peak at just over 27 percent of the roadway’s intended

capacity. The freeway carries no freight traffic and does little to

augment the regional freeway network. Transforming the freeway into a

boulevard could net the city 17 new acres of publicly-controlled land,

creating a dozen connections between West Oakland and downtown where there

are currently five. Removing the freeway would remove a barrier to Jack

London Square, better connecting that neighborhood with both downtown and

West Oakland, said Chris Sensenig, the founder of Connect Oakland. City

officials also see the corridor as a possible route for a second transbay

tube crossing for BART, Caltrain and high-speed rail, Sensenig said. The

below-grade route could be built at the same time the freeway is converted

into a boulevard, or, because that project is likely decades away, it

could create a space underground for the transit lines, when and if that

project comes to fruition. BART included funds in its $3.5 billion bond

measure, which voters approved in November 2016, for a possible study of a

second transbay tube, an idea that has germinated in regional

transportation circles for decades.

(Source: Mercury News, 1/30/2017)

However, the community is not completely on-board with

removal of I-980. The historical argument for getting rid of it assumes

the freeway is a legacy of mid-century attempts to build barriers around

white middle-class neighborhoods, or as a wrecking ball to replace

“urban blight.” That’s true of several major freeways,

but the story of I-980 isn’t so clear cut. By the time the state of

California finally finished building it in 1985, the residents of West

Oakland had come on board. At that point, the community wanted this

freeway. Today, some of those same residents find themselves wary of

another major public works project in their backyard. And that means

activists’ best intentions are colliding with a community that might

prefer to be left alone. In West Oakland, reactions ranged from skepticism

to outright scorn. To comprehend why old timers from this historically

black neighborhood are so dubious, you have to understand two seemingly

conflicting things: that West Oakland has been repeatedly screwed over by

infrastructure projects and that the history of I-980 freeway deviates

from that pattern. Some of the people who initially balk at the idea of

tearing up the freeway become more interested after they consider what

could replace it. Over the past few years, Oakland’s city government

has been holding meetings on the future of the 980 corridor to capture

what residents want. Residents have turned up at the meetings with lots of

ideas for better uses of the land, like bus lanes, parks, and affordable

housing. Some see the response as an encouraging sign: People in the

community may embrace the idea of replacing the freeway, if they get to

choose what comes next.

(Source: SF Streetsblog, 4/17/2019)

In May 2021, it was reported that, the $2.3 trillion

infrastructure proposal President Joe Biden rolled out in Spring 2021

includes $20 billion in funding for projects to “reconnect

neighborhoods cut off by historic investments,” which his

administration argues would be a step toward correcting the Interstate system’s history of tearing through and segregating Black and Latino

neighborhoods in cities across the country. Additionally, Congress is also

considering funding for freeway removal projects as part of a separate

federal highway bill. Further, Senate Democrats have proposed legislation

to create a federal grant program that would award money to those

projects; in a statement touting the bill, California Sen. Alex Padilla

singled out I-980 as a potential candidate. In 2017 the freeway was named

in the top 10 list of urban freeways to tear down in a report by the The

Congress for the New Urbanism, which described I-980 as a blight on the

community. Caltrans, which hasn’t taken a position on the

freeway’s future, is seeking funding for a study that would consider

turning it into a surface street, among other potential changes. The

short, sunken 2-mile I-980 was completed in 1985 and bisects Oakland's

downtown, separating the city’s busy Broadway and Telegraph

corridors from the largely Black and working-class neighborhoods of West

Oakland. The freeway has long been criticized for ruining West Oakland,

isolating the historic neighborhood, and sending it into several decades

of decline. The concern is acute in West Oakland, which was split in two

for decades by both I-980 and the double-decker Cypress freeway section of

I-880. There are no exact plans for what would be built on the I-980 site

at this point. How the project unfolds also depends on BART, which

envisions building a second transbay crossing that could use the freeway

route for a path through Oakland. If removal is approved (and that's a

large "if"), it will take a decade — if not much longer — for

a new streetscape to take the freeway’s place. The plan endorsed by

Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and Connect Oakland would convert the southern

half of I-980 — between I-880 and Grand Avenue — from a

freeway to a four-lane surface street, much like Octavia Boulevard along

San Francisco’s former Central Freeway route. The northern half of

I-980 above Grand Avenue would stay essentially the same. But the ultimate

question is: who would benefit from this change? Reconnecting the

community would not necessarily benefit the black residents of Oakland. As

more White and well-off residents move into new apartment buildings

downtown and historic Victorians in West Oakland — and while many

long-time Black residents struggle to stay amid the Bay Area’s

housing crisis — there is deep skepticism about the plans.

“It’s going to appear like now you’re doing this to

bring new people to Oakland, who are going to be White,” said Roger

Clay Jr., a retired attorney who filed a federal lawsuit that held up the

freeway’s construction in the 1970s. “You’re not doing

this for people who live here now.” Clay represented the people who

lived in the 503 homes that were torn down or moved to make room for the

freeway. His lawsuit delayed construction until Caltrans agreed to build

replacement housing for people being displaced and to change the

freeway’s design from an elevated structure that would roar overhead

to the trench drivers pass through today, limiting noise in the

surrounding neighborhoods. He said the neighbors were mostly satisfied

with the compromise. Clay also worries about the question that faces every

freeway removal effort: More than 100,000 cars passed through Interstate 980 per day before the pandemic, according to Caltrans – can a

surface street handle that many drivers? [And, if one looks at the

concerns coming from the I-710 corridor efforts, there will be

environmental issues related to particulate matter from the removal as

well]

(Source: $Mercury News, 5/11/2021; SFGate, 5/12/2021)

In February 2023, it was reported that the city of

Oakland and Caltrans received $680,000 in federal money to study ways to

reconnect areas divided by I-980. A range of options will be considered

for using or crossing the I-980 corridor. Caltrans officials said all

options are on the table including demolishing the freeway. Caltrans plans

to hire a consultant this year to study the options for crossing or using

the corridor it expects the study will take two to four years to complete.

The funding is part of the Reconnecting Communities Pilot program through

the U.S. Department of Transportation. The other cities receiving funds

are San Jose, Long Beach, Pasadena and Fresno. The pilot program was

established in the nation's Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which passed in

2021. Construction on I-980 began in the 1960s, but wasn’t completed

until 1985. The roughly 2-mile stretch was meant to provide East Bay

motorists taking I-580 and Route 24 with a direct connection to I-880,

past the Oakland airport to San Jose. For many, I-980 is the quickest

route to Jack London Square. But the highway project led to the

destruction of over 500 homes, nearly two dozen businesses and several

churches. While planners had envisioned a connection to a second transbay

bridge linking San Francisco to Route 24, that span was never built. Past

efforts to convert the highway to a tree-laden city street have

consistently fallen short. Even a project included in President Joe

Biden’s $2.3 trillion infrastructure proposal in 2021 was later left

out of the approved spending package.

(Source: CBS Bay Area, 2/24/2023; East Bay Times, 2/28/2023)

In October 2023, it was reported that Caltrans plans to

start holding public information meetings in January 2024 to

“identify a new concept and vision for transportation and land

use” of the freeway. Once they’ve gotten input from the

public, Caltrans will study the viability of different ideas. This is

expected to happen in the fall of 2026. There are many options for the

I-980’s future. It could be ripped out entirely, kept as is, or even

capped and turned into a bigger version of New York’s High Line

park. At this stage, Caltrans’ Vision 980 team said they

don’t want to influence the public about what kinds of ideas are

more realistic or what would be a better use for the freeway. I-980 was

built as a potential connector to a second Bay Bridge, but a second

crossing was never constructed. Oakland residents were divided from the

start about the freeway, with many people who lived in downtown and West

Oakland opposing it. Many people have said for decades that it was a

mistake to build it. Some Oakland residents do not support the removal of

I-980. They say new housing development near downtown would reinforce

gentrification. Many Black residents generally mistrust the impacts that

changes to major infrastructure can have on their communities.

(Source: Oaklandside, 10/30/2023)

Exit Information

Exit Information Other WWW Links

Other WWW Links Naming

Naming Route 980 from Route 880 to 17th Street in Oakland

is named the "John B. Williams Freeway". John B. Williams (1917

– October 13, 1976) was a city planner for Oakland in the 1960s and

1970s. He was head of the Oakland Redevelopment Agency and Oakland's

Office of Community Development from 1964 to 1976. Mr. Williams was

responsible for the redevelopment of Oakland's downtown business district,

including the creation of the City Center project. The plaza connecting

City Center with the 12th Street BART station is named for him. Mr.

Williams died of cancer on October 13, 1976, at the age of 59. Named

by Assembly Concurrent Resolution 52, Chapter 61 in 1977.

Route 980 from Route 880 to 17th Street in Oakland

is named the "John B. Williams Freeway". John B. Williams (1917

– October 13, 1976) was a city planner for Oakland in the 1960s and

1970s. He was head of the Oakland Redevelopment Agency and Oakland's

Office of Community Development from 1964 to 1976. Mr. Williams was

responsible for the redevelopment of Oakland's downtown business district,

including the creation of the City Center project. The plaza connecting

City Center with the 12th Street BART station is named for him. Mr.

Williams died of cancer on October 13, 1976, at the age of 59. Named

by Assembly Concurrent Resolution 52, Chapter 61 in 1977.

(Image source: East Bay Yesterday)

I-980 is also known as the "Grove-Shafter Freeway". This name comes from the streets that the freeway paralleled between the Nimitz Freeway (I-880) and the Warren Freeway (Route 13). In the 1980s, Grove Street was renamed Martin Luther King, Jr. Way. Shafter Street runs from MacArthur Boulevard to the Rockridge BART station.

Interstate Submissions

Interstate SubmissionsApproved as 139(a) non-chargeable interstate in July 1976; Freeway.

Classified Landcaped Freeway

Classified Landcaped FreewayThe following segments are designated as Classified Landscaped Freeway:

| County | Route | Starting PM | Ending PM |

| Alameda | 980 | 0.33 | 1.13 |

| Alameda | 980 | 1.17 | 2.04 |

Freeway

Freeway[SHC 253.1] Entire route. Added to the Freeway and Expressway system in 1959.

Statistics

StatisticsOverall statistics for Route 980:

Route 905

Route 905

Return to State Routes

Return to State Routes

© 1996-2020 Daniel P. Faigin.

Maintained by: Daniel P. Faigin

<webmaster@cahighways.org>.