Click here for a key to the symbols used. An explanation of acronyms may be found at the bottom of the page.

Routing

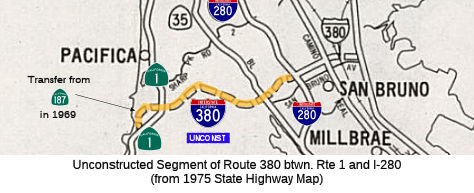

Routing From Route 1 near Pacifica to Route 280 in San Bruno.

From Route 1 near Pacifica to Route 280 in San Bruno.

Post 1964 Signage History

Post 1964 Signage HistoryIn 1969, Chapter 294 defined Route 380 via a transfer from Route 186 as “(a) Route 1 near Pacifica to Route 280 in San Bruno. (b) Route 280 in San Bruno to Route 101 in the vicinity of the San Francisco International Airport. (c) Route 101 in the vicinity of the San Francisco International Airport to Route 87.” This segment remains as defined in 1963. In 1970, Chapter 1473 deleted segment (c)

This segment would have been signed Route 380, as it was never planned to be part of the Interstate system. It would have curled through the hills, crossed Route 1, and continued slightly west before curving south to meet Route 1 again. Terrain and seismic problems (the route would cross over the San Andreas Fault) are what killed this segment of freeway. There has been talk in times past of extending 380 to Skyline Blvd, but no serious proposal has come forth for that.

According to Chris Sampang, the Sneath Lane/San Bruno

Avenue exit off of I-280 (both southbound and northbound) has several

signs of the planned interchange to Route 380 west:

According to Chris Sampang, the Sneath Lane/San Bruno

Avenue exit off of I-280 (both southbound and northbound) has several

signs of the planned interchange to Route 380 west:

Through analysis of maps, Chris has identified a possible routing: I-380 would've continued west of the current Y interchange with I-280 first through a path between Claremont Drive and Crestmoor Drive headed to Skyline Boulevard (Route 35). Route 380 would've met near the San Bruno Avenue and Skyline Boulevard junction; most of the possible ROW is currently either forested or parkland. West of Route 35, Route 380 would've crossed the San Bruno City Limit and straddled it on the south side, following trails in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area in Sweeney Ridge as it entered Pacifica. It would follow some paved trails to the junction of Mori's Point Road, Bradford Way, and Route 1; this just also happens to be the current south end of the Route 1 freeway (and may imply that this south end of the Route 1 freeway was to have been directly connected into Route 380). Past Route 1, Route 380 would head southwest at a 20 degree angle or so away from Mori Point but towards the coast; at the coast, the freeway would make its southward turn back to Route 1. Another map that illustrates this quite well can be found here.

In March 2021, there was an interesting article on what was lost during

construction of the freeways. In the late 1960s, community members blocked

I-380 from being extended to the coast (as noted above). During this time,

the Division of Highways simply appraised and took whatever was in the

path. Among the properties taken for I-380 was a naval base across the

street from the Tanforan racetrack. Some 81 homes were taken, among them

one on Seventh Avenue in San Bruno for $10,760 in 1967.

(Source: Climate Online, 3/16/2021)

Status

Status Part (1) is unconstructed. According to the 2013 Traversable Routing Report, the traversable local streets are San Bruno Avenue and

Sharp Parks Road, but no local roads adequately fit the description of a

state highway. The freeway routing was rescinded effective 3/29/1979. The

city of Pacifica was to improve Sharp Park Road but the proposed

improvements do not meet state standards.

Part (1) is unconstructed. According to the 2013 Traversable Routing Report, the traversable local streets are San Bruno Avenue and

Sharp Parks Road, but no local roads adequately fit the description of a

state highway. The freeway routing was rescinded effective 3/29/1979. The

city of Pacifica was to improve Sharp Park Road but the proposed

improvements do not meet state standards.

Pre 1964 Signage History

Pre 1964 Signage HistoryThis route was LRN 229, defined in 1947.

Naming

Naming The Caltrans "Naming" document indicates that this section is named the "Portola Freeway". Gaspar de Portola

was California's first Spanish governor. In 1769 marched north from San

Diego in command of the first party of Europeans to see San Francisco Bay.

This expedition also discovered the Golden Gate and Carquinez Straits. He

founded the presidio at Monterey and aided in establishing Mission San

Carlos. Named by Assembly Concurrent Resolution 113, Chapt. 217 in 1970.

The Caltrans "Naming" document indicates that this section is named the "Portola Freeway". Gaspar de Portola

was California's first Spanish governor. In 1769 marched north from San

Diego in command of the first party of Europeans to see San Francisco Bay.

This expedition also discovered the Golden Gate and Carquinez Straits. He

founded the presidio at Monterey and aided in establishing Mission San

Carlos. Named by Assembly Concurrent Resolution 113, Chapt. 217 in 1970.

(Image source: SLO Tribune)

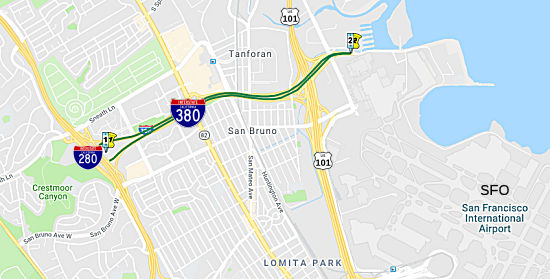

From Route 280 in San Bruno to Route 101 in the vicinity of the San Francisco

International Airport.

From Route 280 in San Bruno to Route 101 in the vicinity of the San Francisco

International Airport.

Post 1964 Signage History

Post 1964 Signage HistoryIn 1969, Chapter 294 defined Route 380 via a transfer from Route 186 as “(a) Route 1 near Pacifica to Route 280 in San Bruno. (b) Route 280 in San Bruno to Route 101 in the vicinity of the San Francisco International Airport. (c) Route 101 in the vicinity of the San Francisco International Airport to Route 87.” This segment remains as defined in 1963. In 1970, Chapter 1473 deleted segment (c)

This segment was authorized for interstate construction by the December 1968 Federal Aid Highway Act, which provided $31.2 milllion for construction of the 1.6 mile segment.

Pre 1964 Signage History

Pre 1964 Signage HistoryThis route was LRN 229, defined in 1947.

Status

StatusThe interchange with Route 280 is "beefier" than usual because of the original planned continuation to Pacifica.

After the construction of the Bay Bridge in 1933, San Francisco began considering duplicating the bridge and running a

second one further south across the bay. Enter Frank Lloyd Wright, the

famed organic architect whose idea and design for a second Bay Bridge

never came to fruition. The noted architect hated the idea of a second

steel structure similar to the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

Partnering with engineer Jaroslav J. Polivka, Wright proposed a concrete

"Butterfly Bridge,” spanning from Army Street (now Cesar Chavez) and

Third Street to its eastern terminus on Bay Farm Island, just north of the

Oakland Airport. Wright and Polivka saw steel truss bridges as extravagant

and obsolete, so the design was all reinforced concrete, resting on a

series of giant hollow almond-shaped piers—which they claimed to be

earthquake-proof construction. Long curved arms would carry six lanes of

traffic and two pedestrian walkways, supported by two arches connected by

a butterfly-shaped garden park (!) as “a pleasant relief and perhaps

a stopping point for the traffic.” The Butterfly Bridge project lost

steam after plans for the underwater—and vastly more

important—Transbay Tube were unveiled, a project that connected BART

from San Francisco to Oakland.

After the construction of the Bay Bridge in 1933, San Francisco began considering duplicating the bridge and running a

second one further south across the bay. Enter Frank Lloyd Wright, the

famed organic architect whose idea and design for a second Bay Bridge

never came to fruition. The noted architect hated the idea of a second

steel structure similar to the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

Partnering with engineer Jaroslav J. Polivka, Wright proposed a concrete

"Butterfly Bridge,” spanning from Army Street (now Cesar Chavez) and

Third Street to its eastern terminus on Bay Farm Island, just north of the

Oakland Airport. Wright and Polivka saw steel truss bridges as extravagant

and obsolete, so the design was all reinforced concrete, resting on a

series of giant hollow almond-shaped piers—which they claimed to be

earthquake-proof construction. Long curved arms would carry six lanes of

traffic and two pedestrian walkways, supported by two arches connected by

a butterfly-shaped garden park (!) as “a pleasant relief and perhaps

a stopping point for the traffic.” The Butterfly Bridge project lost

steam after plans for the underwater—and vastly more

important—Transbay Tube were unveiled, a project that connected BART

from San Francisco to Oakland.

(Source: Curbed SF, 12/8/2017)

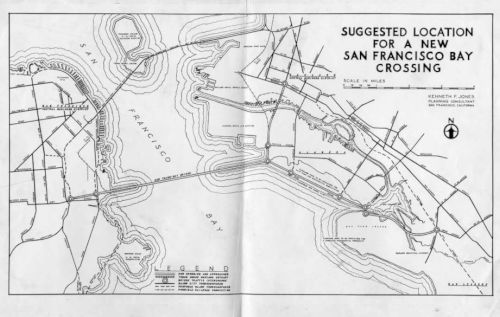

Rep. Richard J. Welch of San Francisco believed that

another span was not only a good idea, but a necessity. The

Chronicle’s May 1, 1946, edition reported that a joint Army-Navy

board of engineers was brought in to respond to the controversy and rule

on whether plans would proceed. Why an Army-Navy board? Army permission

was needed before a navigable waterway could be bridged or dammed, and the

Navy, with many installations in the Bay Area, had expressed opposition to

another Bay Bridge. The recommendation was for a low-level, six-lane

combination trestle and tube from the foot of Army Street in San Francisco

to the foot of Fifth Street in Alameda. “Immediate”

construction was urged. The next day’s Chronicle read:

“Another bridge between San Francisco and the East Bay was assured

yesterday.” The figure to the right shows the New Trans-Bay Bridge

proposal, submitted by Kenneth B. Jones to the Army-Navy board, would exit

San Francisco at Army Street and arrive in the East Bay just south of the

Alameda Naval Air Station.

(Source: SF Chronicle; 12/11/2017)

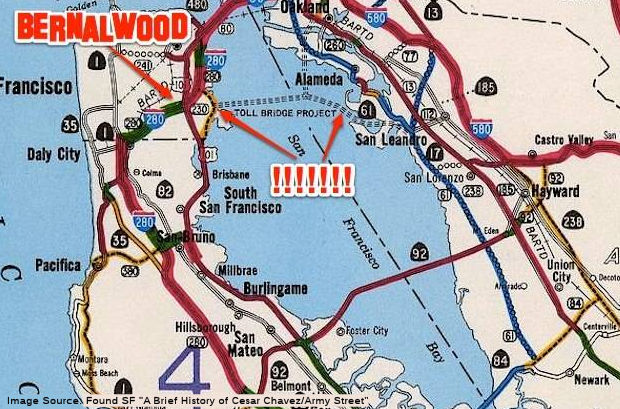

![[Southern Crossing]](maps/southern_crossing.jpg) This map shows the proposed Southern Crossing. This would have been an additional crossing S of the

Bay Bridge, terminating in Oakland (two approaches in Oakland: one along

Alameda and one along Doolittle to the I-880/Hegenberger interchange). The

history of the Southern Crossing goes back at least to 1948, when the

state department of public works prepared a report on additional toll

crossings of San Francisco Bay. This report noted "Because of the

increasing congestion on the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, the

California Toll Bridge Authority, on Oct 30, 1945, directed the Department

of Public Works to make comprehensive studies for another bay crossing

between SF and the East Bay cites. On Jan 31, 1947, the department

recommended construction of an additional bridge just north of and

parallel to the existing bridge—a plan which is now known as the

Parallel Bridge." This report provided an estimated cost for the Parallel

Bridge of $155,014, 000, and an estimate for the Southern Crossing of

$178, 421, 000. The original concept of the Southern Crossing is

illustrated to the right. There's an extensive discussion of the Southern

Crossing and the Parallel Crossing in the November-December 1947 issue of California Highways and Public Works. There's also a discussion on how the Trafficways report showed this version of the

Southern Crossing, and how the intent was to have Army Street feed into

it, on the Found SF page "A Brief History of Cesar Chavez/Army Street".

This map shows the proposed Southern Crossing. This would have been an additional crossing S of the

Bay Bridge, terminating in Oakland (two approaches in Oakland: one along

Alameda and one along Doolittle to the I-880/Hegenberger interchange). The

history of the Southern Crossing goes back at least to 1948, when the

state department of public works prepared a report on additional toll

crossings of San Francisco Bay. This report noted "Because of the

increasing congestion on the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, the

California Toll Bridge Authority, on Oct 30, 1945, directed the Department

of Public Works to make comprehensive studies for another bay crossing

between SF and the East Bay cites. On Jan 31, 1947, the department

recommended construction of an additional bridge just north of and

parallel to the existing bridge—a plan which is now known as the

Parallel Bridge." This report provided an estimated cost for the Parallel

Bridge of $155,014, 000, and an estimate for the Southern Crossing of

$178, 421, 000. The original concept of the Southern Crossing is

illustrated to the right. There's an extensive discussion of the Southern

Crossing and the Parallel Crossing in the November-December 1947 issue of California Highways and Public Works. There's also a discussion on how the Trafficways report showed this version of the

Southern Crossing, and how the intent was to have Army Street feed into

it, on the Found SF page "A Brief History of Cesar Chavez/Army Street".

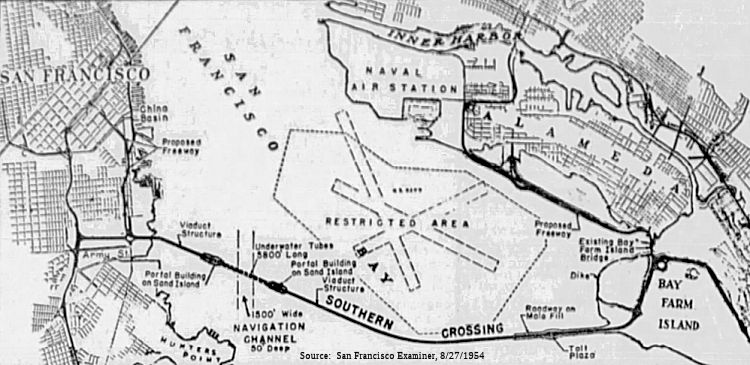

In 1954, it was reported that the plan for the Southern Crossing had changed

again. The western terminus would be in the vicinity of Third and Army in

San Francisco, and the eastern terminus would be on Bay Farm Island in

Alameda County. In 1954, the State Dept of Public Works applied to the

Army Corps of Engineers for permission to construct the crossing. Approval

was granted 4/8/1954 to construct a causeway-tube crossing on an alignment bowed southwards. The plan was for a six-lane tube 7.7 mi in length. Starting in San Francisco, there would be a trestle viaduct approx 5,300' long to a sand island, where traffic would enter one of three 5,800' tubes. They would emerge at another sand island, continue across a low concrete trestle viaduct 22,000' long and then to a 6,000' earthen mole to the SW shore of Bay Farm Island. The route would connect on the Western side with the Bayshore (US 101) Freeway between 25th and 26th Streets and between Tennessee Street and the Embarcadero (I-280) Freeway. The east bay side would connect with the Posey and Webster Street Tubes (Route 260). It was estimated that the project would take 65,000 tons of reinforcing steel; 1 million cubic yards of concrete; 1.5 million barrels of cement; 10,000 tons of structural steel; and 14 million cubic yards of sand. In 1957, it was reported that a study showed that the crossing would not be financially feasible at a toll rate of 25¢, and that it would not be possible to finance construction.

In 1954, it was reported that the plan for the Southern Crossing had changed

again. The western terminus would be in the vicinity of Third and Army in

San Francisco, and the eastern terminus would be on Bay Farm Island in

Alameda County. In 1954, the State Dept of Public Works applied to the

Army Corps of Engineers for permission to construct the crossing. Approval

was granted 4/8/1954 to construct a causeway-tube crossing on an alignment bowed southwards. The plan was for a six-lane tube 7.7 mi in length. Starting in San Francisco, there would be a trestle viaduct approx 5,300' long to a sand island, where traffic would enter one of three 5,800' tubes. They would emerge at another sand island, continue across a low concrete trestle viaduct 22,000' long and then to a 6,000' earthen mole to the SW shore of Bay Farm Island. The route would connect on the Western side with the Bayshore (US 101) Freeway between 25th and 26th Streets and between Tennessee Street and the Embarcadero (I-280) Freeway. The east bay side would connect with the Posey and Webster Street Tubes (Route 260). It was estimated that the project would take 65,000 tons of reinforcing steel; 1 million cubic yards of concrete; 1.5 million barrels of cement; 10,000 tons of structural steel; and 14 million cubic yards of sand. In 1957, it was reported that a study showed that the crossing would not be financially feasible at a toll rate of 25¢, and that it would not be possible to finance construction.

(Image source: San Francisco Examiner, 8/27/1954 via Joel Windmiller, 2/13/2023)

Later plans had the route originating from the east side of the bay near Bay Farm Island (fed by a new interstate, I-980), crossing to the west side, and landing on the San Francisco peninsula in the Bayview neighborhood, at Hunters Point, where it would connect with I-280. The vision was to provide East Bay motorists on I-580 and Route 24 with a direct connection to I-280. In 1961, the Southern Crossing bridge came close to construction, but environmental activists concerned about the environmental degradation of the Bay prevented the project from moving forward. Even though the bridge was dead, construction of I-980 moved ahead in the heart of Oakland, starting over two decades of work that would ultimately divide Black residents in West Oakland from downtown and demolish over 500 homes and nearly two dozen businesses and churches.

(Source: Transportation for America, 3/8/2023)

In 1971, a bill for the construction of the Southern

Crossing was passed in the California State Assembly by both houses but

vetoed by then-Governor Ronald Reagan, who believed that the citizens of

the Bay Area should weigh in on the decision to construct such an

expensive and controversial infrastructure project. Voters rejected a bond

measure in 1972 that would have paid for the construction of the bridge

via a toll increase on existing bridge infrastructure by a three-to-one

margin. Without the bridge, the finally completed, roughly two-mile

stretch of I-980 ended abruptly at 18th Street. See the page on I-980 for

the issues revolving around that segment. The page on the history of Army

Street and Cesar Chavez notes that in 1971, even after most other San

Francisco freeway projects have been abandoned, California Freeway

Planning Map still showed the proposed Southern Crossing (however, the map

image does not appear to be from the state highway map of 1970).

Evidently, Army Street/Cesar Chavez would have been a major feeder into

the Southern Crossing. In support of this, in 1973, the Army Street/US 101

Spaghetti Bowl interchange was built, replacing the roundabout that

previously linked Army with Potrero Ave. and Bayshore Blvd. The new

interchange was intended in part to serve traffic coming from and going to

a future Southern Crossing:

In 1971, a bill for the construction of the Southern

Crossing was passed in the California State Assembly by both houses but

vetoed by then-Governor Ronald Reagan, who believed that the citizens of

the Bay Area should weigh in on the decision to construct such an

expensive and controversial infrastructure project. Voters rejected a bond

measure in 1972 that would have paid for the construction of the bridge

via a toll increase on existing bridge infrastructure by a three-to-one

margin. Without the bridge, the finally completed, roughly two-mile

stretch of I-980 ended abruptly at 18th Street. See the page on I-980 for

the issues revolving around that segment. The page on the history of Army

Street and Cesar Chavez notes that in 1971, even after most other San

Francisco freeway projects have been abandoned, California Freeway

Planning Map still showed the proposed Southern Crossing (however, the map

image does not appear to be from the state highway map of 1970).

Evidently, Army Street/Cesar Chavez would have been a major feeder into

the Southern Crossing. In support of this, in 1973, the Army Street/US 101

Spaghetti Bowl interchange was built, replacing the roundabout that

previously linked Army with Potrero Ave. and Bayshore Blvd. The new

interchange was intended in part to serve traffic coming from and going to

a future Southern Crossing:

(Source: Transportation for America, 3/8/2023; FoundSF "A Brief History of Cesar Chavez/Army Street", August 2023)

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors cited an increase in traffic that it said would bring more smog and congestion to the city. Foley brushed aside the votes. San Francisco had for 10 years supported the plan, he argued, and the Bridge Authority didn’t need the city’s approval anyway. Powerful Assemblyman Leo Ryan weighed in, saying the second crossing would be a disaster for the recently opened BART system and a “blow to the tenuous ecological balance of the bay.” A bond measure on the ballot in 1972 would have funded a planned crossing from Hunters Point and Alameda, but voters rejected it.

The University of California, Berkeley, has an online library exhibit that contains a lot of information about this unbuilt crossing; you can find it at http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/news_events/bridge/ . This would have come approximately from the Route 82/Route 87 junction It is possible that Route 87 may have been the Southern Crossing.

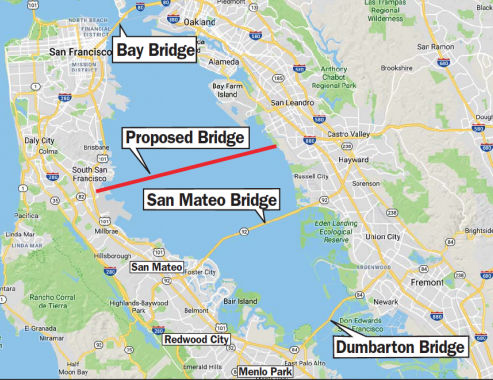

I-380/I-238 Proposals

There were later Southern Crossing proposals, for example, one in 1996 proposed extending Route 238 to Daly City. Note that the Southern Crossing isn't dead yet. In July 2001, the California Transportion Commission was funding a study regarding to the feasibility of a Southern Crossing. However, this later version would have run from I-380 at the top of the San Francisco International Airport to the bottom of the Oakland Airport, for a much longer crossing.

The San Francisco Bay Crossings Study, dated June 2002, had construction of a new Mid-Bay Bridge (mistakenly called by some the "Southern Crossing", but the actual proposed Southern Crossing was further north) as Alternative 4. This bridge would have connected I-380 to Route 238 in the East Bay. This alternative assumed a connection between I-380 on the west end, just N of San Francisco International Airport, and Route 238. The connection would cross at one of the widest points in the San Francisco Bay. The overall length of the structure would be 13.5 miles, and be the 6th longest bridge, just behind Florida's Sunshine Skyway Bridge. It the main span was connected as 850 feet as proposed in the study, it would be the 5th longest orthotropic steel box girder span in the world.

The crossing itself would consiste of the bridge structure from the East Toll Plaza to the apporaches at the I-380 interchange. There would be an east and west causeway, and a High Bridge spanning the shipping channel. The causeways would be trestle structures similar to the existing San Mateo Bridge. The SFO Airport Obstruction Clearance Line and glide path would preclude a cable-stayed, suspension, or extradosed type bridge; hence, the High Bridge would be comprised mostly of long-span precast concrete segmental box girders. These would have to be lightweight, as the girder structure would be at the maximum span range (750-850 ft) for this type of bridge in a high seismic region. The causeways would be approximately 12.1 miles long, with the high bridge being approximately 1.1 miles long. The capital cost estimates for this are phenominal: costs for the alternative, including the crossing, approach, right of way acquisition, and transit bus rolling stock, would run from $6.646 billion to $8.245 billion dollars, with operation and maintenance costs of $35 million annually.

In September 2002, the CTC had on its agenda TCRP Project #11, requested by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), to fund $1.8M for completing the feasibility and financial studies for the new crossing alternatives. The TCRP allocated $5,000,000.

In November 2010, the "Southern Crossing" proved itself

the proposal that wouldn't die. In early November 2010, saying its mission

is to look at long-term options for traffic relief, the Bay Area Toll

Authority's oversight committee considered authorizing a $400,000 study on

the Southern Crossing Bridge between I-238 in San Lorenzo and I-380 in San

Bruno. The odds of the bridge are low: There was no clamor to build the

bridge after a study in 2002 estimated the price tag at $8.2 billion. The

money for the study would come from tolls collected on seven state-owned

toll bridges in the region. Planning consultants hired by the authority

would take about six months to update technical information about the

Southern Crossing bridge and alternatives for reducing traffic congestion.

The toll authority will use the study findings to decide whether to

conduct a second, more detailed study with recommendations on whether to

build the new bridge. The bridge study would examine the feasibility of

developing express bus lanes or rail service on the bridge in addition to

lanes for car traffic. Plans for a new bridge spanning the bay have been

considered, and rejected for environmental and other concerns, at least

five times since 1947. They range from a mirror-image twin of the Bay

Bridge to an eight-lane highway and BART bridge from San Leandro to San

Bruno and a two-legged bridge shaped like the letter "Y" with one leg to

Alameda, the other to San Leandro. Information on this study can be found

here.

In November 2010, the "Southern Crossing" proved itself

the proposal that wouldn't die. In early November 2010, saying its mission

is to look at long-term options for traffic relief, the Bay Area Toll

Authority's oversight committee considered authorizing a $400,000 study on

the Southern Crossing Bridge between I-238 in San Lorenzo and I-380 in San

Bruno. The odds of the bridge are low: There was no clamor to build the

bridge after a study in 2002 estimated the price tag at $8.2 billion. The

money for the study would come from tolls collected on seven state-owned

toll bridges in the region. Planning consultants hired by the authority

would take about six months to update technical information about the

Southern Crossing bridge and alternatives for reducing traffic congestion.

The toll authority will use the study findings to decide whether to

conduct a second, more detailed study with recommendations on whether to

build the new bridge. The bridge study would examine the feasibility of

developing express bus lanes or rail service on the bridge in addition to

lanes for car traffic. Plans for a new bridge spanning the bay have been

considered, and rejected for environmental and other concerns, at least

five times since 1947. They range from a mirror-image twin of the Bay

Bridge to an eight-lane highway and BART bridge from San Leandro to San

Bruno and a two-legged bridge shaped like the letter "Y" with one leg to

Alameda, the other to San Leandro. Information on this study can be found

here.

MTC looked into the southern crossing in 2012, where the bridge would connect Route 238 in Hayward to I-380 in San Bruno. The Hayward to San Bruno bridge, along with a BART tunnel, would cost up to $12.4 billion, according to a May 2012 presentation to the Bay Area Toll Authority. Rentschler said while Feinstein’s wish for a southern connection is “compelling,” the bigger challenge is getting traffic to flow on either side of the new bridge. According to the May 2012 presentation, at least 61,300 people a day would use the new bridge, and around 27,100 of those would be new transbay trips. Reinstating the defunct Dumbarton Rail corridor — an abandoned rail line that goes from Redwood City to Menlo Park and then across the Bay on a run down railroad trestle — and improving the San Mateo Bridge are alternatives to an entirely new bridge.

In December 2017, the Southern Crossing

reappeared in a proposal from Senator Dianne Feinstein, who renewed her

call for a new east-west transbay bridge somewhere south of the

always-congested Bay Bridge. Feinstein, D-Calif., has repeatedly called

since 2000 for a Southern Crossing, an idea that has been around since the

1940s, but has been rejected in recent years as too costly and

environmentally problematic. On Wednesday, joined by Rep. Mark DeSaulnier,

D-Concord, she sent a letter to Steve Heminger, executive director of the

Metropolitan Transportation Commission. The letter chastised the

commission for not moving forward on a new transbay span. Its authors said

it would relieve Bay Bridge congestion, and that it should be funded by

Regional Measure 3, a ballot measure — written, but not yet

scheduled — that could raise tolls on state-owned toll bridges by as

much as $3. MTC spokesman Randy Rentschler acknowledged receipt of the

letter. He said the commission appreciated the acknowledgment of the need

for major investment in Bay Area infrastructure. The letter, he said, will

be taken seriously. But Rentschler did not commit to undertaking a new

bay-crossing study, pointing out that it’s not on the list of

projects the Legislature approved when it agreed to let the Bay Area vote

on Regional Measure 3 to raise its tolls. Several versions of a Southern

Crossing have been proposed through the decades, none of which has been

undertaken. After Feinstein floated the idea in 2000, the commission

undertook a two-year study of what it would cost. It concluded that

building a bridge from Route 238 in Hayward to the Peninsula would cost

$8.2 billion, saying that was cheaper than a new BART tube between San

Francisco and Oakland but still costlier than the Bay Area could probably

afford. Another two-year study, completed in 2012, estimated the cost of a

bridge that would carry both cars and some form of transit, at $12.4

billion. Both studies assumed a new crossing that would be built from

I-380, in San Bruno, to I-238 in San Leandro. The letter from Feinstein

and DeSaulnier included no specifics but did mention “the need for

an additional route for both BART and vehicular traffic.” On

Wednesday the SamTrans board approved the Dumbarton Corridor study, which

is a plan that calls for increasing the frequency of buses across the

current Dumbarton bridge and rebuilding the rail bridge for Caltrain or

BART.

In December 2017, the Southern Crossing

reappeared in a proposal from Senator Dianne Feinstein, who renewed her

call for a new east-west transbay bridge somewhere south of the

always-congested Bay Bridge. Feinstein, D-Calif., has repeatedly called

since 2000 for a Southern Crossing, an idea that has been around since the

1940s, but has been rejected in recent years as too costly and

environmentally problematic. On Wednesday, joined by Rep. Mark DeSaulnier,

D-Concord, she sent a letter to Steve Heminger, executive director of the

Metropolitan Transportation Commission. The letter chastised the

commission for not moving forward on a new transbay span. Its authors said

it would relieve Bay Bridge congestion, and that it should be funded by

Regional Measure 3, a ballot measure — written, but not yet

scheduled — that could raise tolls on state-owned toll bridges by as

much as $3. MTC spokesman Randy Rentschler acknowledged receipt of the

letter. He said the commission appreciated the acknowledgment of the need

for major investment in Bay Area infrastructure. The letter, he said, will

be taken seriously. But Rentschler did not commit to undertaking a new

bay-crossing study, pointing out that it’s not on the list of

projects the Legislature approved when it agreed to let the Bay Area vote

on Regional Measure 3 to raise its tolls. Several versions of a Southern

Crossing have been proposed through the decades, none of which has been

undertaken. After Feinstein floated the idea in 2000, the commission

undertook a two-year study of what it would cost. It concluded that

building a bridge from Route 238 in Hayward to the Peninsula would cost

$8.2 billion, saying that was cheaper than a new BART tube between San

Francisco and Oakland but still costlier than the Bay Area could probably

afford. Another two-year study, completed in 2012, estimated the cost of a

bridge that would carry both cars and some form of transit, at $12.4

billion. Both studies assumed a new crossing that would be built from

I-380, in San Bruno, to I-238 in San Leandro. The letter from Feinstein

and DeSaulnier included no specifics but did mention “the need for

an additional route for both BART and vehicular traffic.” On

Wednesday the SamTrans board approved the Dumbarton Corridor study, which

is a plan that calls for increasing the frequency of buses across the

current Dumbarton bridge and rebuilding the rail bridge for Caltrain or

BART.

(Source: SF Chronicle, 12/6/2017; PaloAlto

Daily Post, 12/10/2017; Curbed SF, 12/8/2017; SFChronicle,

12/11/2017)

Note: The Southern Crossing would have connected I-380

with I-238, and then I-580, at the point where Route 238 met Route 61.

(Source: KGO 7, 11/13/2018)

In November 2019, it was reported that the Southern

Crossing is still not dead. With traffic getting worse, and rush hour now

spanning several hours, Sen. Dianne Feinstein and East Bay Rep. Mark

DeSaulnier have warmed up an idea that’s stewed since the 1940s:

building another bridge south of the first one. It would most likely link

Route 238 in San Lorenzo to I-380 near San Francisco International

Airport, combining a roadway for cars with some form of mass transit, like

BART. Feinstein and DeSaulnier say it would relieve congestion on both the

Bay and San Mateo bridges. The lawmakers’ push comes as Bay Area

leaders rally to put a transportation mega-tax measure on the November

2020 ballot, trying to generate $100 billion over four decades. One of the

key projects under discussion is a new transbay crossing. But the goals of

transportation leaders are evolving, and many are eyeing concepts that

don’t cater to automobiles. BART and Capitol Corridor are studying

the possibility of a second underwater Transbay Tube, which could include

rail tracks for Amtrak or Caltrain. Meanwhile, some mass transit

enthusiasts envision a bridge that sends bullet trains across the water.

Feinstein and DeSaulnier requested the report two years ago when the

commission and other groups were pressing for Regional Measure 3, a series

of bridge-toll hikes to fund transportation projects throughout the Bay

Area. In November 2019, MTC released its most recent report on the matter,

“Crossings: Transformative Investments for an Uncertain

Future.” It analyzed seven alternatives for a new span. The first

two options centered on automobiles: a new southern bridge with two

traffic lanes and one carpool lane in each direction, or a rebuilt and

widened San Mateo Bridge. Also considered was a BART-automobile hybrid,

consisting of twin tunnels beneath the bay — one for cars, one for

trains. Two concepts were BART tubes from Alameda to downtown San

Francisco, with one of them adding an extension to the city’s

Mission Bay. Another was a rail bridge for Caltrain and Amtrak, and a

final one combined a new BART tube with a conventional rail crossing. MTC

recommended advancing everything except the car-only ideas, saying they

provided limited relief for drivers and no help for rush-hour crowds that

already overwhelm BART. The car proposals would increase greenhouse gas

emissions, the agency said, and could prompt more collisions. By contrast,

the rail ideas carried environmental benefits and should be pursued, the

report said. As for a car tunnel, commission staff was not enthusiastic.

Engineers would have to build new freeway interchanges on both sides of

the bay that could displace low-income residents and divide communities,

the report said. The project could cost up to $53 billion. DeSaulnier

criticized the findings, saying the commission failed to look at the

entire Interstate 80-to-Highway 101 corridor, from the Carquinez Bridge to

San Francisco International Airport. In a joint statement, he and

Feinstein argued that a Southern Crossing for cars and transit would

“do more than any other project to alleviate congestion in the

region.” Officials at MTC said the current state of the freeways is

intolerable but that a new highway bridge would do little to loosen up

traffic. “The proposed bridge is hemmed in by freeways that are

maxed out on both sides,” Rentschler said. “We could build a

20-lane bridge, and it would still perform poorly,” absent widening

the freeways.

(Source: SF Chronicle, 11/15/2019)

Naming

Naming Interstate 380 from Route 101 to Interstate 280

is named the "Portola" Freeway. It is named for Gaspar de Portola,

California's first Spanish governor. In 1769 marched north from San Diego

in command of the first party ofEuropeans to see San Francisco Bay. This

expedition also discovered the Golden Gate and Carquinez Straits. He

founded the presidio at Monterey and aided inestablishing Mission San

Carlos. Named by Assembly Concurrent Resolution 113, Chapt. 217 in 1970.

Interstate 380 from Route 101 to Interstate 280

is named the "Portola" Freeway. It is named for Gaspar de Portola,

California's first Spanish governor. In 1769 marched north from San Diego

in command of the first party ofEuropeans to see San Francisco Bay. This

expedition also discovered the Golden Gate and Carquinez Straits. He

founded the presidio at Monterey and aided inestablishing Mission San

Carlos. Named by Assembly Concurrent Resolution 113, Chapt. 217 in 1970.

(Image source: SLO Tribune)

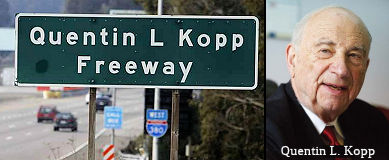

I-380 in San Mateo County is also signed as the "Quentin

L. Kopp Freeway". Quentin Lewis Kopp (born in August 1928 in

Syracuse NY) is an American politician and retired judge. He served as a

member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and in the California

State Senate. Kopp ran unsuccessfully for Mayor of San Francisco in 1979

against Dianne Feinstein. Kopp advocated for the extension of BART to SFO

which was completed in 2003. Kopp was elected to the San Francisco

Board of Supervisors in 1971 and served until 1986, representing the West

Portal neighborhood. In 1986, Kopp ran for California State Senate.

Kopp won by one percentage point. He won reelection in 1990 and 1994. Term

limits prevented Kopp from seeking reelection in 1998. In 1998, Republican

then-Governor Pete Wilson appointed Kopp to a judgeship in San Mateo

County. He served in that capacity until his retirement in 2004. During

his time in the California State Senate, and afterward, Kopp, together

with Mike Nevin, helped push through the BART extension to San Francisco

International Airport with an airport station. In 1994, Kopp qualified an

advisory ballot measure in San Francisco, Measure I, which advocated for a

station inside the International Terminal. This resulted in the BART

extension being built as a triangle, with the vertices being the San Bruno

station at Tanforan Shopping Center, and not on the Caltrain Right-of-Way,

Millbrae (Caltrain terminal) and SFO International Terminal. To get to all

the stations on the extension, the BART train has to reverse at least

once. The alternative rejected by Kopp was single station at San Bruno,

California where the SFO People mover, BART and Caltrain would share a

common station. The extension of the SFO People Mover across to the

station was to be paid for as part of the traffic mitigation for the new

International Terminal. Kopp served as a member of the California High

Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA). As Chairman he worked to lead statewide

efforts to develop an 800-mile high speed train network linking northern

and southern California with fast, reliable, and environmentally friendly

trains capable of traveling at up to 220 mph (350 km/h). To help fund the

project, Kopp led efforts to pass Proposition 1A in November 2008 - a

$9.95 billion bond that has created the momentum that has led to the

project receiving billions in federal funds.

I-380 in San Mateo County is also signed as the "Quentin

L. Kopp Freeway". Quentin Lewis Kopp (born in August 1928 in

Syracuse NY) is an American politician and retired judge. He served as a

member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and in the California

State Senate. Kopp ran unsuccessfully for Mayor of San Francisco in 1979

against Dianne Feinstein. Kopp advocated for the extension of BART to SFO

which was completed in 2003. Kopp was elected to the San Francisco

Board of Supervisors in 1971 and served until 1986, representing the West

Portal neighborhood. In 1986, Kopp ran for California State Senate.

Kopp won by one percentage point. He won reelection in 1990 and 1994. Term

limits prevented Kopp from seeking reelection in 1998. In 1998, Republican

then-Governor Pete Wilson appointed Kopp to a judgeship in San Mateo

County. He served in that capacity until his retirement in 2004. During

his time in the California State Senate, and afterward, Kopp, together

with Mike Nevin, helped push through the BART extension to San Francisco

International Airport with an airport station. In 1994, Kopp qualified an

advisory ballot measure in San Francisco, Measure I, which advocated for a

station inside the International Terminal. This resulted in the BART

extension being built as a triangle, with the vertices being the San Bruno

station at Tanforan Shopping Center, and not on the Caltrain Right-of-Way,

Millbrae (Caltrain terminal) and SFO International Terminal. To get to all

the stations on the extension, the BART train has to reverse at least

once. The alternative rejected by Kopp was single station at San Bruno,

California where the SFO People mover, BART and Caltrain would share a

common station. The extension of the SFO People Mover across to the

station was to be paid for as part of the traffic mitigation for the new

International Terminal. Kopp served as a member of the California High

Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA). As Chairman he worked to lead statewide

efforts to develop an 800-mile high speed train network linking northern

and southern California with fast, reliable, and environmentally friendly

trains capable of traveling at up to 220 mph (350 km/h). To help fund the

project, Kopp led efforts to pass Proposition 1A in November 2008 - a

$9.95 billion bond that has created the momentum that has led to the

project receiving billions in federal funds.

(Image source: SFGate; SF Examiner; Additional information: Wikipedia)

Classified Landcaped Freeway

Classified Landcaped FreewayThe following segments are designated as Classified Landscaped Freeway:

| County | Route | Starting PM | Ending PM |

| San Mateo | 380 | 4.71 | 6.22 |

| San Mateo | 380 | 6.37 | 6.62 |

Interstate Submissions

Interstate SubmissionsApproved as chargeable interstate in December 1968; Freeway.

In October 1958, the designation I-380 was proposed for the Embarcadero Freeway, which was later approved as I-480, downgraded to Route 480, and ultimately relinquished and destroyed.

Exit Information

Exit Information Other WWW Links

Other WWW Links Freeway

Freeway[SHC 253.1] Entire route. Added to the Freeway and Expressway system in 1959.

Statistics

StatisticsOverall statistics for I-380:

© 1996-2020 Daniel P. Faigin.

Maintained by: Daniel P. Faigin

<webmaster@cahighways.org>.