Click here for a key to the symbols used. An explanation of acronyms may be found at the bottom of the page.

Routing

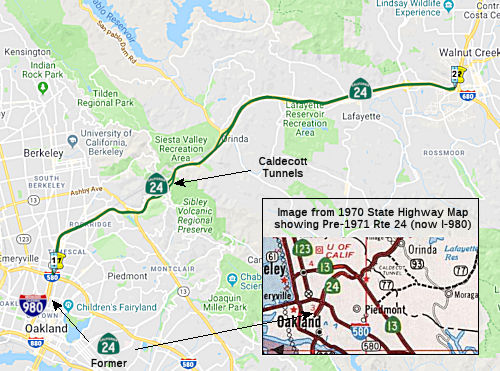

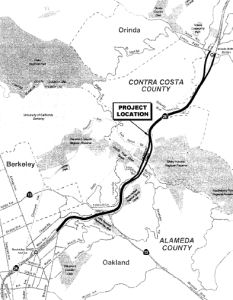

Routing From Route 580 in Oakland to Route 680 in Walnut Creek.

From Route 580 in Oakland to Route 680 in Walnut Creek.

Post 1964 Signage History

Post 1964 Signage HistoryIn 1963, there was an additional segment before this one: "Route 17 near Castro Street in Oakland to Route 580". In 1981, Chapter 292 deleted this segment, moving that routing to I-980. That segment was originally LRN 226, defined in 1959.

This segment (former (b), now (a)) remains as defined in 1963.

In 1966, construction was completed on Route 24 (Grove-Shafter Freeway)

between 0.4 mi W of Route 13 in Oakland and the Caldecott Tunnel in

Berkeley (1.3 mi).

(Source: CHPW Nov/Dec 1966)

The Gateway Boulevard viaduct on Route 24 west of Orinda may have been

constructed for the intersection of a future freeway, according to one

account that I read. I have not yet confirmed this. The viaduct is located

near where Route 93 was planned to intersect Route 24.

(Source: Mail from Jason A. Bezis, 7/2/2002)

Pre 1964 Signage History

Pre 1964 Signage History In 1931, a routing from a proposed Oakland tunnel to Walnut Creek was proposed. This appears to correspond to the eventual Route 24,

however, this segment was not included in the original signage of Route 24

defined in 1934. See below for a full discussion of the original Route 24.

In 1931, a routing from a proposed Oakland tunnel to Walnut Creek was proposed. This appears to correspond to the eventual Route 24,

however, this segment was not included in the original signage of Route 24

defined in 1934. See below for a full discussion of the original Route 24.

California Highways and Public

Works, in April 1931, reported that Joint Highway District Number 13,

composed of Alameda and Contra Costa counties, had organized for

construction of a public highway and tunnel to supersede the pre-1931

narrow, crooked and inadequate 'Tunnel road in Alameda County and to

improve the Contra Costa County road from the tunnel to the town of Walnut

Creek. The state proposed for inclusion as a state highway that portion of

the route in Contra Costa County between. the tunnel and Walnut Creek, a

distance of 9.6 miles. Based on the volume and class of traffic on the

pre-1931 tunnel road and on the other highways leading into Oakland (one

from Livermore via Hayward, the other from Martinez through Crockett), and

estimating the effect of better facilities in the Walnut Creek area, the

conservative 12 hour traffic was anticipated for 1940 as equivalent to a

24 hour traffic of 17K vehicles on Sundays and 10K on weekdays. The state

felt this route qualified for state inclusion based on volume, importance,

and character of 1931 and future traffic.

California Highways and Public

Works, in April 1931, reported that Joint Highway District Number 13,

composed of Alameda and Contra Costa counties, had organized for

construction of a public highway and tunnel to supersede the pre-1931

narrow, crooked and inadequate 'Tunnel road in Alameda County and to

improve the Contra Costa County road from the tunnel to the town of Walnut

Creek. The state proposed for inclusion as a state highway that portion of

the route in Contra Costa County between. the tunnel and Walnut Creek, a

distance of 9.6 miles. Based on the volume and class of traffic on the

pre-1931 tunnel road and on the other highways leading into Oakland (one

from Livermore via Hayward, the other from Martinez through Crockett), and

estimating the effect of better facilities in the Walnut Creek area, the

conservative 12 hour traffic was anticipated for 1940 as equivalent to a

24 hour traffic of 17K vehicles on Sundays and 10K on weekdays. The state

felt this route qualified for state inclusion based on volume, importance,

and character of 1931 and future traffic.

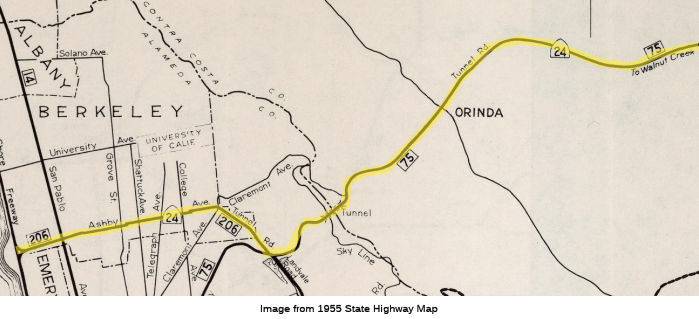

The routing has been signed as part of Route 4 (LRN 75, defined in 1931) before the Route 24 signage. In October 1935, it was reported that the Route 24 signage had been extended south from Sacramento to Oakland, via Isleton, Antioch, and Walnut Creek. This may have been related to the opening of the Broadway Tunnels. Note that portions of what was Route 24 are present-day Route 242 and Route 4.

The original routing for Route 24 included what is now Route 13 (renumbered in 1964) between the present Route 13/Route 24 interchange in Oakland and I-80. That segment was LRN 206, and ran along Ashby Avenue. It was added to the state highway system in 1935. However, the actual highway did not exist until the Broadway (later called "Caldecott") Tunnel opened in 1937.

The Ashby routing was part of the larger Bay Bridge project which included construction of the Eastshore Highway with which Ashby connected. On the other side of the hills, Route 24 was routed on Mount Diablo Boulevard.

Caldecott Tunnels and Predecessors

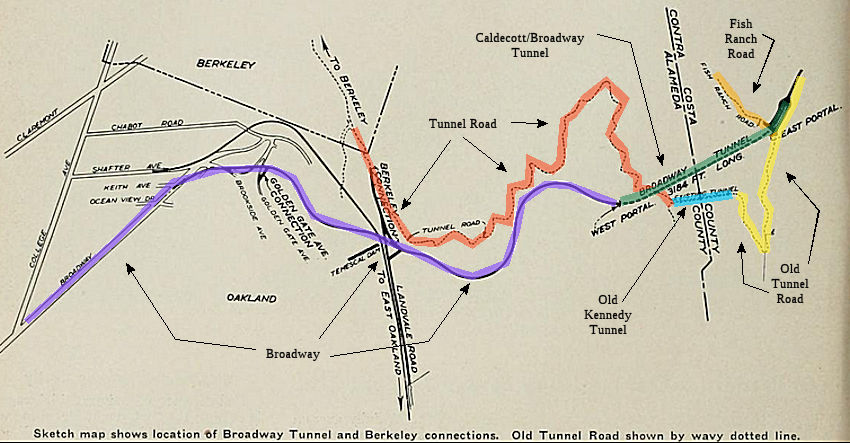

The original routing between Oakland and Lafayette over

the Berkeley Hills of Alameda County followed a steep ascent via what is

now Telegraph Avenue and Claremont Avenue. Upon cresting the Berkley

Hills this road would have followed what is now Fish Ranch Road in Contra

Costa County. The first known concept for a tunnel through the

Berkeley Hills emerged in 1860 but was rejected by the populace in Alameda

County and Contra Costa County. Another concept emerged in 1871 as

an extension of Broadway via a vaguely described path which would emerge

somewhere near San Pablo Creek in Contra Costa County. This 1871

concept would eventually emerge as the route of a choice for a tunnel and

would sporadically be under construction during the following

decades. Eventually the tunnel construction was taken up by the

Merchants Exchange of Oakland which procured the funding and permits to

complete construction.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), “Former California State Route 24 through the Kennedy Tunnel and Old Tunnel Road”, January 2021)

The resulting "Inter County Tunnel" was opened November

4th, 1903, and was later renamed as the "Kennedy Tunnel". It was a

single-lane, timber-supported, 1000' structure that served as a conduit

until 1937, when the first Caldecott bores were completed and dedicated.

The tunnel closed in the 1940s. Lafayette residents protested the tunnel,

predicting that it would increase competition for land and price them out

of the market. But private and county money eventually financed a tunnel.

The Kennedy Tunnel had a four-foot elbow in the middle; diggers had

miscalculated the meet-up. The tunnel was also called the the Broadway

Tunnel (although that name was also used for the Caldecott, at one time).

The western entrance was near Tunnel Road and Skyline Boulevard. The

eastern entrance is at the end of Old Tunnel Road. At the east entrance, a

residence owned by the East Bay Regional Park District stands on the

former site of the Canary Cottage cafe. The original tunnel has been

abandoned and the ends sealed.

The resulting "Inter County Tunnel" was opened November

4th, 1903, and was later renamed as the "Kennedy Tunnel". It was a

single-lane, timber-supported, 1000' structure that served as a conduit

until 1937, when the first Caldecott bores were completed and dedicated.

The tunnel closed in the 1940s. Lafayette residents protested the tunnel,

predicting that it would increase competition for land and price them out

of the market. But private and county money eventually financed a tunnel.

The Kennedy Tunnel had a four-foot elbow in the middle; diggers had

miscalculated the meet-up. The tunnel was also called the the Broadway

Tunnel (although that name was also used for the Caldecott, at one time).

The western entrance was near Tunnel Road and Skyline Boulevard. The

eastern entrance is at the end of Old Tunnel Road. At the east entrance, a

residence owned by the East Bay Regional Park District stands on the

former site of the Canary Cottage cafe. The original tunnel has been

abandoned and the ends sealed.

(Image source: December 1937 CHPW)

Broadway was chosen for LRN 75 (Route 24) over versus

Ashby Avenue (LRN 206 / Route 13) as Broadway, at the time, connected

directly with Tunnel Road whereas Ashby Avenue did not yet connect.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), “Former California State Route 24 through the Kennedy Tunnel and Old Tunnel Road”, January 2021)

In 1937, the Caldecott Tunnels (called the Broadway Low-Level Tunnels) opened, a twin-bore tunnel designed to replace the dark, dank, single-bore Kennedy Tunnel 300 feet above it. At that time, some 30,000 cars were passing through Kennedy every week. The twin tunnels, each 3000' feet, were concrete lined, lighted, and had forced air ventilation. Note that as the two tunnels were curved at the end and joined one another at a single portal building at each end, there was a belief that there was just a single tunnel with a thin concrete supporting wall. In reality, the roadways are 150' apart except at the two ends. Each of the tunnels has a 22' wide roadway and a with of 26' 8" between the sidewalls. Each bore carried one direction of traffic.

Development in Contra Costa boomed and a third bore opened in 1964, outfitted with a system of tubes that popped out of the pavement and allowed workers to change directions of the middle bore to handle traffic, which generally flowed west in the morning and east in the evening. Modern standards required that the highways at each end of the tunnels be widened and straightened and that the third bore be made wider than the first two. As the third tunnel was to be considerably larger than the two older tunnels, it was not possible to adapt the original plans to the new location. The third tunnel has a 28 foot wide roadway and is 34 feet 6 inches wide between the sidewalk. The vertical clearance is 17 feet above the pavement, compared with the 14 feet 10 inches in the two older bores. In addition to the larger size of the tunnel itself, there are numerous other features which are new or improved. The entire length of the roadway is illuminated by a continuous line of fluorescent lights on each side of the ceiling. Extra lights are placed for a distance of 300 feet at each end so that there is a gradual transition in the daytime in order to allow drivers' eyes to adjust to the change from the bright sunlight outside and the artificial light in the center of the tunnel. Emergency power facilities have also been installed for use in the event that there is a power loss from the serving utilities. A new transverse system of ventilation is being used. Fresh air is taken in at the westerly portal building and carried along a duct above the roadway. It is discharged into the roadway section through openings at one side of the ceiling. The fresh air mixes with exhaust fumes from the vehicles, and is drawn out through exhaust ports on the opposite side of the ceiling, then carried to the westerly portal building and discharged straight up into the atmosphere. The two fresh air and two exhaust blowers have a capacity of a half-million cubic feet of air per minute. On October 6, 1964, dignitaries from throughout the area assembled to dedicate Tunnel III to the name and further honor of Thomas E. Caldecott.

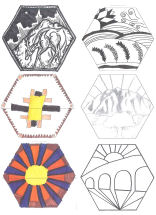

Adorning the original Caldecott

Tunnel bores are medallions that were designed by Henry Meyers, the

official Alameda County architect in the 1930s. One depicts people facing

each other to symbolize how the tunnel joins the residents of Contra Costa

and Alameda counties; another shows a car headlight exiting a tunnel.

Meyers may have had a lot of help from draftsman George Klinkhardt in

designing the tunnel exterior and medallions, a Caltrans report suggests.

In fact, Klinkhardt may have designed the entire tunnel exterior, the

reports says. Meyers, who grew up in Livermore and whose Alameda home has

been turned into a museum, designed more than 200 buildings, including

Highland Hospital in Oakland, the Posey Tube in Alameda and 10 veterans

memorial buildings, including the ones in Livermore and Pleasanton. In

2012, Caltrans held a student design competition to design medallions to

adorn the new 4th bore. The competition will be limited to students from

Contra Costa and Alameda counties. The six new hexagon-shaped medallions

-- each about 36 inches high -- will be public art for the ages.

Adorning the original Caldecott

Tunnel bores are medallions that were designed by Henry Meyers, the

official Alameda County architect in the 1930s. One depicts people facing

each other to symbolize how the tunnel joins the residents of Contra Costa

and Alameda counties; another shows a car headlight exiting a tunnel.

Meyers may have had a lot of help from draftsman George Klinkhardt in

designing the tunnel exterior and medallions, a Caltrans report suggests.

In fact, Klinkhardt may have designed the entire tunnel exterior, the

reports says. Meyers, who grew up in Livermore and whose Alameda home has

been turned into a museum, designed more than 200 buildings, including

Highland Hospital in Oakland, the Posey Tube in Alameda and 10 veterans

memorial buildings, including the ones in Livermore and Pleasanton. In

2012, Caltrans held a student design competition to design medallions to

adorn the new 4th bore. The competition will be limited to students from

Contra Costa and Alameda counties. The six new hexagon-shaped medallions

-- each about 36 inches high -- will be public art for the ages.

In July 2012, the updated artwork was chosen. Specifically, six students’ winning images of Mount Diablo, rugged foothills, and the sun will be built into the exterior of the Caldecott Tunnel Fourth Bore.

Status

StatusThis route is constructed as a freeway.

The 2022 SHOPP included the following new project: 04-CC-24 R0.01. PPNO

0480B; ProjID 0414000011; EA 0J540. Route 24 In Orinda, at the Caldecott

Tunnel № 28-0015R, 28-0015, and 28-0015L. Rehabilitate Caldecott

Tunnel Bores 1, 2, and 3. Total Project Cost: $69,487K. Begin Con:

10/1/2026.

(Source: “2022 State Highway Operation

And Protection Program, Fiscal Years 2022-23 through 2025-26”,

March 17, 2022)

4th Bore - Caldecott Tunnel (~ ALA R5.858 to CC R0.416)

In September 2000, the California

Transportation Commission considered (TCRP Project #15) a $15 million

allocation for phase one of construction of a fourth bore tunnel with

additional lanes for the Caldecott Tunnel (~ ALA R5.858 to CC R0.416). The

total estimated cost is $185 million. This project was requested by the

Metropolitan Transportation Commission. Bore 3, constructed in the early

1960's (long after bores 1 and 2) was actually constructed with the fourth

bore being kept in mind. As evidenced by the tunnel, stub lanes (on both

ends of the tunnel) do actually indicate a 4th bore was in

mind, as small strips of pavement (wide enough for 2 lanes) spur from the

existing highway before fading off into the bushes and trees before

entering the tunnel. This is currently planned to complete construction in

late 2012. Funding was extended for this in September 2005.

In September 2000, the California

Transportation Commission considered (TCRP Project #15) a $15 million

allocation for phase one of construction of a fourth bore tunnel with

additional lanes for the Caldecott Tunnel (~ ALA R5.858 to CC R0.416). The

total estimated cost is $185 million. This project was requested by the

Metropolitan Transportation Commission. Bore 3, constructed in the early

1960's (long after bores 1 and 2) was actually constructed with the fourth

bore being kept in mind. As evidenced by the tunnel, stub lanes (on both

ends of the tunnel) do actually indicate a 4th bore was in

mind, as small strips of pavement (wide enough for 2 lanes) spur from the

existing highway before fading off into the bushes and trees before

entering the tunnel. This is currently planned to complete construction in

late 2012. Funding was extended for this in September 2005.

The SAFETEA-LU act, enacted in August 2005 as the reauthorization of TEA-21, provided the following expenditures on or near this route:

In February 2006, the CTC noted that the goal of TCRP Project #15 is to improve the movement of people and goods along Route 24 via the Caldecott Tunnels, to improve travel time and therefore reduce delays, and enhance safety of the traveling public and Department maintenance workers. When the environmental process started, seven alternatives were under consideration. Based on several screening criteria, four alternatives were dropped. The elimination of the four alternatives reduced the cost and the Department and the Contra Costa Transportation Authority (CCTA) have identified $5,000,000 of available TCRP funds for other work. In February 2006, the Department and CCTA request that the funds be redistributed to Plans, Specifications, and Estimates. The Draft Environmental Document is being finalized and will be ready for circulation in July 2006. The alternatives being considered are:

The Final EIR was received in December 2007, and the CTC indicated construction is estimated to begin in Fiscal Year 2009-10. The total estimated project cost, capital and support, is $420,000,000. The project is funded from $175,000,000 local funds, $20,000,000 Traffic Congestion Relief Program funds, $1,000,000 Federal Demonstration funds, $18,000,000 in Regional Improvement Program funds, $31,000,000 Interregional Improvement Program funds, and $175,000,000 Corridor Mobility Improvement Account funds. The funding sources were adjusted in June 2008.

In January 2009, Caltrans removed one of the last obstacles preventing it from adding a fourth bore to the Caldecott Tunnel by settling a lawsuit with Oakland residents concerned about the impacts of building the new tunnel. The settlement to the suit by the Caldecott Fourth Bore Coalition calls for Caltrans to:

The settlement was crafted between attorneys for the coalition and Caltrans with pressure from state legislative leaders and Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who wanted to see the fourth bore built as part of his state economic stimulus strategy. He had sought to have the project exempted from the environmental review process, which would have nullified the suit, but that undoubtedly entangled the project in other legal challenges. However, the project may still get caught up in the 2008/2009 Budget mess. The $420 million Caldecott Tunnel project depends on $194.5 million from the transportation infrastructure bonds voters approved in 2006. Plans to hire a contractor to start digging the long-awaited fourth bore this summer were halted Jan. 14 2009, when the California Transportation Commission froze funding for the Caldecott Tunnel and 26 other projects that had been scheduled to receive $293.5 million in state funding. If the governor and the Legislature settle the budget crisis by early February, the fourth bore could receive funding from the transportation commission on Feb. 18 and Caltrans could start the process of hiring a contractor by March 1 - just two to four weeks behind schedule.

At the January 2009 meeting, the CTC deferred to February (and in February, deferred it to March... and in March, to April) discussion about reorganization of this project. The intent is to split the original project into four segments, as follows:

The basic plans for the project are:

In April 2009, the CTC approved funding this project (as a loan against future bonds) from 2009 Stimulus funds. It was advertised for construction in May 2009.

In late January 2010, politicians and transportation

officials gathered in an enclosed and heated tent in Orinda, not far from

the tunnel, to celebrate the official groundbreaking for the $420 million

fourth bore. After an hour and a half of speeches, they grabbed

gold-painted shovels and dug from a pile of dirt trucked in for the

ceremony. Actual construction was already under way with contractors

clearing brush and preparing to erect retaining walls on both sides of the

tunnel and a sound wall on the west end. In June 2010, workers expect to

begin digging the new tunnel from both ends. Tunneling crews will dig the

new hole in the Oakland hills in segments, first digging out the top of

the tunnel, then building the tunnel gradually by excavating a segment and

bolstering it with braces and sprayed concrete. They will also dig seven

cross-passages to the third bore - to provide emergency exits. The

completed bore will be 41 feet, 3 inches wide and 3,389 feet long.

Caltrans officials expect the project to create about 5,000 jobs during

the four years of construction. Nearly half of the money to pay for the

project is coming from federal stimulus funds. John Porcari, deputy

secretary of the U.S. Department of Transportation, said the fourth bore

is the largest recipient of stimulus funds for infrastructure in the

nation.

(Source: "Work begins on Caldecott Tunnel's 4th bore", San Francisco Chronicle, 1/23/2010)

Before the actual tunnel construction starts in July

2010, there has been significant preparatory work. Since January 2010,

construction crews have been busy building retaining walls to keep the

hills from collapsing onto Route 24. To build the retaining walls, crews

are boring holes about 2 1/2 feet across, 8 feet apart and 36 feet to 97

feet deep. The bottoms of the holes are filled with concrete, then steel

I-beams are dropped in. When all the beams are in place, the dirt in front

of them will be removed and wooden planks will be inserted between the

beams to hold back the hillside. Eventually they'll be covered in

concrete. The crews are also constructing and portal walls that will form

the eastern and western entrances to the new two-lane fourth bore. Just

north of the existing westbound tunnel, workers are preparing the concrete

and steel faces through which the digging of the fourth bore will

commence. The face is a series of interlocking columns formed by boring

holes, filling them with concrete, then boring new holes in between, and

filling them with concrete. The walls are then tied together and

strengthened with steel, creating a strong surface to dig through. Walls

on each side of the face are built by covering the soil with concrete then

inserting long, thick steel reinforcement rods into the earth. They're

grouted in place and act like long, strong nails. Workers have also

constructed a $3.5 million charcoal gray temporary sound wall between the

freeway and the apartments and condos on Caldecott Lane, just west of the

tunnel. This wall was constructed by putting I-beams in the ground,

putting huge wooden planks between them, then fastening 2-inch-thick

noise-absorbent plastic pads on both sides. The walls sport slanted tops

pointed toward the freeway. The idea is to trap the noise, light and dust

generated during construction when trucks use the narrow strip between the

freeway and the wall as a staging ground with a concrete plant,

water-treatment facility and dumping area for soils excavated from the

Oakland hills. Additionally, trees have been removed from the hillsides, a

traffic signal is being installed on Upper Broadway, and three electrical

substations are under construction.

(Source: "Caldecott Tunnel fourth bore under construction", San Francisco Chronicle, 5/21/2010)

In his 2006 Strategic Growth Plan, Governor Schwartzenegger proposed completing the Caldecott Tunnel Corridor. In 2007, the CTC recommended using $175M from the Corridor Mobility Improvement Account (CMIA) for the 4th bore.

In July 2010, it was reported that The $420 million excavation of a fourth bore of the Caldecott Tunnel between Orinda and Oakland has opened a door for paleontologists to search for fossils expected to give clues to old life-forms and climate change in the Bay Area. Private paleontologists hired by Caltrans already have found a tooth — likely a remnant of a camel — and dozens of remains of fish scales, plants and other bone bits in dirt and rock dug up, shoved around and shored up in early construction work outside the new bore site. One area considered prime for fossil finds is the Orinda Formation, a jumble of fractured layers of old stream beds and flood plains. The silt and sediment there is ideal for covering up and preserving fossils from creatures that roamed the East Bay 9 million to 10 million years ago in the Miocene period. This is the first time that Caltrans has called in paleontologists to a Bay Area freeway project at its beginning to monitor for fossils. Caltrans said it is paying about $35,000 a month for the paleontological work. The duration of the collection will be shaped by how long the crews keep finding fossils.

In March 2011, it was noted that, after a year of construction, construction crews have dug out more than 900 feet -- or 27 percent -- of the 3,389-foot-long Caldecott Tunnel fourth bore, a project now estimated to cost $391 million after favorable construction bids lowered the cost from $420 million. The 21,665 cubic meters of earth and rock excavated from the Caldecott fourth bore so far would cover a football field 16 feet deep. When the project is finished, the excavated earth would cover a football field 134 feet deep.

In September 2011, the New York Times reported on this construction. It noted that the project was projected to create 4,500 jobs. The work in the tunnel is more dangerous than work in the average tunnel. Safety regulators declared it “gassy” from the start because of the naturally occurring methane gas in the guts of the Berkeley Hills. Anything that could spark an explosion, from cellphones to lighters, is banned from the inside of the tunnel. Because of sections of precariously weak rock, miners must use what is called the New Austrian Tunneling Method, meaning that crews dig just short distances before taking measures to reinforce the tunnel. The digging machine, called a roadheader, is a 130-ton instrument that looks like a metal brontosaurus with a spiked metal rotating head for grinding rock. It is followed by a remote-controlled robot on wheels that sprays a special quick-drying concrete over the newly bored section. With another machine, the miners then drive long steel dowels into the tunnel walls to reinforce them before proceeding. Once the boring is completed, it will take two more years to scoop out the bottom portion, install ventilation, lighting and communication systems, and otherwise transform the rough-hewn hole through the hills into a subterranean stretch of freeway. By the end of 2013, the tunnel be able to accommodate four lanes of traffic in each direction. It will eliminate the need for Caltrans workers to engage in an often futile game of trying to minimize backups by switching the direction of traffic through the center bore at least twice daily, often more frequently.

In November 2011, it was reported that construction of the fourth bore broke through the Orinda hillside, thus connecting the two sections of the tunnel being dug. In January 2012, it was reported that state safety regulators have ruled the fourth bore project is no longer classified as a "gassy" tunnel, where methane and other gases could trigger explosions or fires.

In March 2012, it was reported that a competition was being held to design adornments for the 4th bore. Caltrans announced in late March 2012 the opening of the unusual competition to design six, 36-inch tall architectural medallions that will be cast out of concrete above the entrances to the Caldecott Tunnel fourth bore on Route 24. May 7 2012 was the deadline to submit original art deco drawings, which Caltrans plans to use in designing molds for pouring concrete to form the decorative shapes. The competition was limited to students from kindergarten through high school in schools in Contra Costa and Alameda counties. This is the first student-only architectural design competition Caltrans has used in the Bay Area. Caltrans picked "classic art deco" as the theme after the art style was strongly favored in an agency online poll on six different themes, and was the theme used on the other bores.

In April 2012, it was reported that excavation was taking longer than expected, owing to tough digging conditions. In Fall 2011, a crew of miners and their brontosaurus-like digging machine encountered unexpectedly difficult conditions — including harder rock formations and, in some places, water.

In August 2012, it was reported that the 4th bore was

completed. This bore contained safety features developed as a result of

the crash of a drunk driver inside the Caldecott Tunnel on April 7, 1982.

The crash touched off a chain reaction that turned the third bore into a

2,000-degree tomb and killed seven people. There were no emergency

passages, and the narrow tunnel had no shoulder. There were no traffic

lights, emergency gates or message signs to warn motorists of the fireball

inside, caused when a gasoline tanker burst into flames. Utilizing lessons

leared from this accident, new safety features for the third and fourth

bores include traffic lights and a traffic gate that swings down in

emergencies. The third and fourth bores also will be the first to have an

extensive network of electronic message signs and traffic signals inside;

and unlike the original two bores, the third and fourth will be connected

by seven lighted, 12-foot-wide escape passages. The escape passages are

air pressurized to keep smoke and toxic gases away from fleeing travelers.

Additionally, only the fourth bore has a shoulder, a 10-foot wide swath to

stash damaged vehicles or for fire trucks, ambulances or law enforcement

to access accidents. The Caldecott Tunnel also is safer than it was in

1982 because of a ban on trucking gasoline and other flammable liquids or

poison gases through the tunnel, except between 3 and 5 a.m. Even when the

new bore opens, some safety features will be hidden, such as water lines.

Some will be too small to see, like heat sensors. Most obvious will be 19

ceiling-mounted fans, all capable of churning up 20 mph breezes to sweep

away smoke and gases. The fans are more powerful than those in the other

bores. One new safety feature common to all four bores is a radio override

system that allows tunnel operators to broadcast emergency messages on car

radios, regardless of the station to which they are tuned.

(Source: Contra Costa Times, 10/31/13)

In November 16, 2013, the new fourth bore opened.

Naming

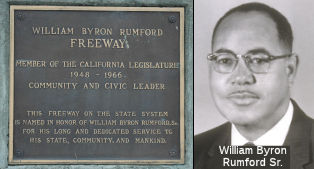

Naming Route 24 from Interstate 580 to the

Caldecott Tunnel (~ALA R1.914 to ALA R5.837) is named the "William

Byron Rumford Freeway". Byron Rumford was a State legislator. Named

by Assembly Concurrent Resolution 137, Chapter 92 in 1980. The dedication

plaque reads: William Byron Rumford Freeway, Member of the California

Legislature 1948-1966, Community and Civic Leader. This freeway on the

state system is named in honor of William Byron Rumford Sr. for his long

and dedicated service to his state, community, and mankind." William Byron

Rumford (February 2, 1908 – June 12, 1986) was a pharmacist,

community leader, and politician. He was the first African American

elected to any public office in Northern California, and the first African

American hired at Highland Hospital. Rumford graduated from a segregated

high school in Arizona in 1926. At 18, he moved to San Francisco and

worked for a year, before attending Sacramento Junior College. The School

of Pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco accepted

Rumford, and he worked his way through school, working as a parking valet

and a doorman at night, and graduated in 1931. While at UCSF Rumford was a

member of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. At the age of 25 William Rumford

passed the State of California employment examination in 1933, at a time

when very few African Americans worked for the State. After passing the

employment exam, Rumford took the California Board of Pharmacy

investigator examination, where he twice passed the written part of the

exam, but was twice failed on the oral portion. Rumford then passed the

examination for California State Venereal Disease investigator, but again

was failed on the oral presentation portion for a third time. Undaunted,

Rumford visited one of the members of the Personnel Board who lived in

Oakland. Christenson, the board member, appealed the Board's decision to

fail Rumford based on the grounds that he was asked irrelevant questions.

Rumford went on to appeal on the grounds that the Board had publicized

statistics that African Americans suffered from sexually transmitted

diseases at a greater rate than other ethnic groups, but had not taken

done anything to improve the situation. Rumford won the appeal and was

granted his California State certification. Rumford became co-owner of a

pharmacy in Berkeley in 1942 at the age of 34, which he later purchased

outright and renamed Rumford's Pharmacy. He tried to continue with his job

at Highland Hospital while running the pharmacy. Eventually, Rumford

decided to leave Highland Hospital, devoting his time fully to the

pharmacy. In addition to his business, Rumford was director of the Red

Cross Oakland chapter, President of the East Bay Health Association, and a

member of the Democratic Central Committee for the Bay Area. In 1944, he

was appointed by Governor Earl Warren to the Rent Control Board. He helped

found the Berkeley Interracial Committee. Rumford served in the California

State Assembly from 1948–1966, with a special focus on in fair

employment, control of air pollution, and fair housing. In 1955, Rumford

first introduced a Fair Housing Act, and in 1963, the California State

Legislature passed the Rumford Fair Housing Act which outlawed restrictive

covenants and the refusal to rent or sell property on the basis of race,

ethnicity, gender, marital status, or physical disability.

Route 24 from Interstate 580 to the

Caldecott Tunnel (~ALA R1.914 to ALA R5.837) is named the "William

Byron Rumford Freeway". Byron Rumford was a State legislator. Named

by Assembly Concurrent Resolution 137, Chapter 92 in 1980. The dedication

plaque reads: William Byron Rumford Freeway, Member of the California

Legislature 1948-1966, Community and Civic Leader. This freeway on the

state system is named in honor of William Byron Rumford Sr. for his long

and dedicated service to his state, community, and mankind." William Byron

Rumford (February 2, 1908 – June 12, 1986) was a pharmacist,

community leader, and politician. He was the first African American

elected to any public office in Northern California, and the first African

American hired at Highland Hospital. Rumford graduated from a segregated

high school in Arizona in 1926. At 18, he moved to San Francisco and

worked for a year, before attending Sacramento Junior College. The School

of Pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco accepted

Rumford, and he worked his way through school, working as a parking valet

and a doorman at night, and graduated in 1931. While at UCSF Rumford was a

member of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. At the age of 25 William Rumford

passed the State of California employment examination in 1933, at a time

when very few African Americans worked for the State. After passing the

employment exam, Rumford took the California Board of Pharmacy

investigator examination, where he twice passed the written part of the

exam, but was twice failed on the oral portion. Rumford then passed the

examination for California State Venereal Disease investigator, but again

was failed on the oral presentation portion for a third time. Undaunted,

Rumford visited one of the members of the Personnel Board who lived in

Oakland. Christenson, the board member, appealed the Board's decision to

fail Rumford based on the grounds that he was asked irrelevant questions.

Rumford went on to appeal on the grounds that the Board had publicized

statistics that African Americans suffered from sexually transmitted

diseases at a greater rate than other ethnic groups, but had not taken

done anything to improve the situation. Rumford won the appeal and was

granted his California State certification. Rumford became co-owner of a

pharmacy in Berkeley in 1942 at the age of 34, which he later purchased

outright and renamed Rumford's Pharmacy. He tried to continue with his job

at Highland Hospital while running the pharmacy. Eventually, Rumford

decided to leave Highland Hospital, devoting his time fully to the

pharmacy. In addition to his business, Rumford was director of the Red

Cross Oakland chapter, President of the East Bay Health Association, and a

member of the Democratic Central Committee for the Bay Area. In 1944, he

was appointed by Governor Earl Warren to the Rent Control Board. He helped

found the Berkeley Interracial Committee. Rumford served in the California

State Assembly from 1948–1966, with a special focus on in fair

employment, control of air pollution, and fair housing. In 1955, Rumford

first introduced a Fair Housing Act, and in 1963, the California State

Legislature passed the Rumford Fair Housing Act which outlawed restrictive

covenants and the refusal to rent or sell property on the basis of race,

ethnicity, gender, marital status, or physical disability.

(Bio: Oakland Wiki; Image source: Read the Plaque; Join California)

This segment is historically part of "El Camino Sierra" (Road to the Mountains). It continues along what is now I-680.

Named Structures

Named StructuresThe “Kennedy Tunnel”, the predecessor tunnel to the Caldecott or Broadway Tunnel, was named for L. W. Kennedy. Kennedy is said to have first conceived the idea of a toll road and tunnel between the counties. He started a company which built a road and began work on a tunnel, but "Work was begun upon the hole in the hill, but a rush of water was struck to the extent that it collapsed the tunnel and the company at the same time." Note that other sources claim that Wright F. Kelsey was the first to propose building a tunnel between the counties.

The "Caldecott Tunnel" (structure 28-015) (~ ALA R5.858 to CC R0.416) on Route 24 between Alameda and Contra Costa Counties was named

for Thomas Edwin Caldecott (July 27, 1878 – July 23, 1951), who was

a pharmacist and politician when the tunnel was built. From 1923,

Caldecott served in politics in Alameda County, California in the San

Francisco Bay Area until 1951. Caldecott was born in Chester, England on

July 27, 1878. Both of his parents were Welsh. The family immigrated to

Toronto, Ontario, Canada about 1882. Caldecott grew up in Canada, and

obtained a pharmacy degree from the University of Toronto in 1900. Thomas

and his brother visited Berkeley, California, and shortly thereafter in

1903, moved their entire family there. That same year, Caldecott bought a

pharmacy at Dwight Way and Shattuck Avenue, later moved to Ashby Avenue

and Adeline Street in the Webb Block, a building which was designated a

local landmark in 2004. Caldecott was elected to the City Council of

Berkeley in 1923. In 1930, he was appointed to fill out the remaining term

of Mayor Michael B. Driver. He then successfully ran for the office of

Mayor in 1931, serving until December 1932. He was then elected as a

supervisor on the Alameda County Board of Supervisors, serving from 1933

until his death in 1951. He was chairman of the board from 1945-1946. In

1948, he formed the Alameda County Highway Committee, "to solve sectional

differences over highway problems." He was also instrumental in

establishing a new Alameda County Juvenile Hall, which was completed after

his death in 1951. Caldecott served as the president of Joint Highway

District 13, which oversaw the construction of the multi-bore Broadway Low

Level Tunnel through the Berkeley Hills east of San Francisco Bay. When

opened in 1937,[14] it was the longest tunnel in the State of California,

and accomplished the opening up of the entire region east of the hills as

a major suburb of the Bay Area. At an event that year, Caldecott was

honored "as the man responsible for the success of the project". In 1941,

Caldecott was publicly commended for his "untiring efforts" in bringing

the project to a successful completion. In 1960, the tunnel was re-named

the "Caldecott Tunnel", in recognition of his leadership on the project.

The tunnel was originally called the "Broadway Low-level" Tunnel

(the former tunnel through the Oakland hills was at a much higher

elevation.) It was built in 1937 and refurbished in 1965, and was named by

Assembly Concurrent Resolution 8 in 1969.

The "Caldecott Tunnel" (structure 28-015) (~ ALA R5.858 to CC R0.416) on Route 24 between Alameda and Contra Costa Counties was named

for Thomas Edwin Caldecott (July 27, 1878 – July 23, 1951), who was

a pharmacist and politician when the tunnel was built. From 1923,

Caldecott served in politics in Alameda County, California in the San

Francisco Bay Area until 1951. Caldecott was born in Chester, England on

July 27, 1878. Both of his parents were Welsh. The family immigrated to

Toronto, Ontario, Canada about 1882. Caldecott grew up in Canada, and

obtained a pharmacy degree from the University of Toronto in 1900. Thomas

and his brother visited Berkeley, California, and shortly thereafter in

1903, moved their entire family there. That same year, Caldecott bought a

pharmacy at Dwight Way and Shattuck Avenue, later moved to Ashby Avenue

and Adeline Street in the Webb Block, a building which was designated a

local landmark in 2004. Caldecott was elected to the City Council of

Berkeley in 1923. In 1930, he was appointed to fill out the remaining term

of Mayor Michael B. Driver. He then successfully ran for the office of

Mayor in 1931, serving until December 1932. He was then elected as a

supervisor on the Alameda County Board of Supervisors, serving from 1933

until his death in 1951. He was chairman of the board from 1945-1946. In

1948, he formed the Alameda County Highway Committee, "to solve sectional

differences over highway problems." He was also instrumental in

establishing a new Alameda County Juvenile Hall, which was completed after

his death in 1951. Caldecott served as the president of Joint Highway

District 13, which oversaw the construction of the multi-bore Broadway Low

Level Tunnel through the Berkeley Hills east of San Francisco Bay. When

opened in 1937,[14] it was the longest tunnel in the State of California,

and accomplished the opening up of the entire region east of the hills as

a major suburb of the Bay Area. At an event that year, Caldecott was

honored "as the man responsible for the success of the project". In 1941,

Caldecott was publicly commended for his "untiring efforts" in bringing

the project to a successful completion. In 1960, the tunnel was re-named

the "Caldecott Tunnel", in recognition of his leadership on the project.

The tunnel was originally called the "Broadway Low-level" Tunnel

(the former tunnel through the Oakland hills was at a much higher

elevation.) It was built in 1937 and refurbished in 1965, and was named by

Assembly Concurrent Resolution 8 in 1969.

(Image source: Oakland Museum; Bio information: Wikipedia)

The fourth bore of the Caldecott Tunnel (Route 24,~ CC R0.071) is named the Representative

Ellen O’Kane Tauscher Memorial Bore. It was named in memory

of Ellen O’Kane Tauscher, a dedicated public servant serving

the 10th Congressional District from 1997–2009. Ellen O’Kane

was born in Newark, New Jersey, in November 1951, the daughter of a

grocery store owner. She earned a degree in early childhood education from

Seton Hall University in 1974. In her mid-20s, she became one of the first

women to hold a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, serving from

1977–79, and during her 14-year Wall Street career, she also served

as an officer of the American Stock Exchange. In 1989, Ellen O’Kane

married William Tauscher and raised a daughter, Katherine. The couple

later divorced. In 1992, Ellen O’Kane Tauscher founded a service for

preemployment screening of childcare providers. She later authored the

Child Care Sourcebook. She also created the Tauscher Foundation, which

donated two hundred thousand dollars ($200,000) to California and Texas

schools to buy computer equipment for elementary education. Ellen

O’Kane Tauscher received her first political experience serving as

the state cochair for Dianne Feinstein’s successful 1992 and 1994

Senate campaigns. In 1996, Ellen O’Kane Tauscher challenged

incumbent California Republican Representative William P. Baker in a newly

created Delta district comprising bedroom communities that are the most

conservative in the San Francisco Bay area. She ran on a platform of gun

control, women’s reproductive rights, and increased spending on

education, along with the reduction of wasteful fiscal spending and

narrowly won, with 49 percent of the vote to Baker’s 47 percent, in

a race with three minor party candidates. In the next two elections,

Representative Tauscher won by slightly more comfortable margins over

Republican candidates, defeating Charles Ball 53 percent to 43 percent and

Claude B. Hutchinson 52 percent to 44 percent. When Representative

Tauscher took her seat in the 105th Congress (1997–1999), she was

assigned to three committees: National Security (later renamed Armed

Services); Science, Space, and Technology; and Transportation and

Infrastructure. In the 106th Congress (1999–2001), Representative

Tauscher resigned her Science, Space, and Technology Committee seat to

focus on her two other assignments, where she remained for the balance of

her career in the House of Representatives. Representative

Tauscher’s committee assignments provided her a national platform

from which she also was able to serve district needs. As a member of the

Armed Services Committee, she outlined an activist role for the United

States in the international arena. Her district was the only one having

two national defense laboratories, Lawrence Livermore and Sandia, and she

secured nearly $200,000,000 in funding for Livermore’s “super

laser” project. Representative Tauscher also had a prominent role as

the senior Democrat on the congressional panel overseeing the National

Nuclear Security Administration, which manages the United States nuclear

weapons program. From her seat on the Transportation and Infrastructure

Committee, Representative Tauscher steered federal funding to improve the

San Francisco Bay area’s badly strained transportation systems,

including $33,000,000 for projects in her district. In 1998, Time magazine

dubbed her moderate Democratic approach to politics

“Tauscherism,” a kind of middle-of-the-road politics that

blended fiscal conservatism with social liberalism and reflected the

political realities of her suburban district, which, until reapportionment

in 2002, was more Republican than Democratic. When the lines were redrawn

by the California Legislature, Representative Tauscher easily won

reelection to a fourth term, with 75 percent of the vote against

Libertarian candidate Sonia E. Harden. In 2004, Representative Tauscher

won reelection with 66 percent of the vote against Republican Jeff

Ketelson, and in 2006 and 2008 voters returned her to office with 66

percent and 65 percent of the vote, respectively. On May 5, 2009,

Representative Tauscher was nominated by President Barack Obama to be the

Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security. On

June 25, 2009, Representative Tauscher was confirmed to the position of

Under Secretary of State by a voice vote of the United States Senate and

resigned her seat in Congress the next day to take the position.

Representative Tauscher represented the United States at numerous

international meetings and negotiations, including setting into motion the

New START Treaty, the first major nuclear arms reduction and limitation

agreement with Russia in over two decades, which was signed in 2009, and

ratified in 2010. Representative Tauscher served the Obama administration

as Under Secretary of State until February 7, 2012, when she was named

Special Envoy for Strategic Stability and Missile Defense, a position she

held until August 31, 2012. In 2013, Representative Tauscher was elected

chairperson of the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, a group of 28

global retailers, and led efforts that created industry safety standards

in response to the fire and collapse of a Bangladeshi garment factory that

killed over 1,000 workers. In March 2013, Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr.,

appointed Representative Tauscher as the chair of the Governor’s

Military Council and was tasked with expanding defense industry jobs and

investment in California. On September 17, 2013, Representative Tauscher

was named as an independent member of the Board of Governors for Lawrence

Livermore National Laboratory and Los Alamos National Laboratory, and

served as chair of the Board of Governors beginning on February 16, 2018.

On June 2, 2017, Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr., appointed Representative

Tauscher to serve on the Board of Regents of the University of California.

She passed away in 2019. Named by Senate Concurrent Resolution 77, Res.

Chapter 32, 09/11/20.

The fourth bore of the Caldecott Tunnel (Route 24,~ CC R0.071) is named the Representative

Ellen O’Kane Tauscher Memorial Bore. It was named in memory

of Ellen O’Kane Tauscher, a dedicated public servant serving

the 10th Congressional District from 1997–2009. Ellen O’Kane

was born in Newark, New Jersey, in November 1951, the daughter of a

grocery store owner. She earned a degree in early childhood education from

Seton Hall University in 1974. In her mid-20s, she became one of the first

women to hold a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, serving from

1977–79, and during her 14-year Wall Street career, she also served

as an officer of the American Stock Exchange. In 1989, Ellen O’Kane

married William Tauscher and raised a daughter, Katherine. The couple

later divorced. In 1992, Ellen O’Kane Tauscher founded a service for

preemployment screening of childcare providers. She later authored the

Child Care Sourcebook. She also created the Tauscher Foundation, which

donated two hundred thousand dollars ($200,000) to California and Texas

schools to buy computer equipment for elementary education. Ellen

O’Kane Tauscher received her first political experience serving as

the state cochair for Dianne Feinstein’s successful 1992 and 1994

Senate campaigns. In 1996, Ellen O’Kane Tauscher challenged

incumbent California Republican Representative William P. Baker in a newly

created Delta district comprising bedroom communities that are the most

conservative in the San Francisco Bay area. She ran on a platform of gun

control, women’s reproductive rights, and increased spending on

education, along with the reduction of wasteful fiscal spending and

narrowly won, with 49 percent of the vote to Baker’s 47 percent, in

a race with three minor party candidates. In the next two elections,

Representative Tauscher won by slightly more comfortable margins over

Republican candidates, defeating Charles Ball 53 percent to 43 percent and

Claude B. Hutchinson 52 percent to 44 percent. When Representative

Tauscher took her seat in the 105th Congress (1997–1999), she was

assigned to three committees: National Security (later renamed Armed

Services); Science, Space, and Technology; and Transportation and

Infrastructure. In the 106th Congress (1999–2001), Representative

Tauscher resigned her Science, Space, and Technology Committee seat to

focus on her two other assignments, where she remained for the balance of

her career in the House of Representatives. Representative

Tauscher’s committee assignments provided her a national platform

from which she also was able to serve district needs. As a member of the

Armed Services Committee, she outlined an activist role for the United

States in the international arena. Her district was the only one having

two national defense laboratories, Lawrence Livermore and Sandia, and she

secured nearly $200,000,000 in funding for Livermore’s “super

laser” project. Representative Tauscher also had a prominent role as

the senior Democrat on the congressional panel overseeing the National

Nuclear Security Administration, which manages the United States nuclear

weapons program. From her seat on the Transportation and Infrastructure

Committee, Representative Tauscher steered federal funding to improve the

San Francisco Bay area’s badly strained transportation systems,

including $33,000,000 for projects in her district. In 1998, Time magazine

dubbed her moderate Democratic approach to politics

“Tauscherism,” a kind of middle-of-the-road politics that

blended fiscal conservatism with social liberalism and reflected the

political realities of her suburban district, which, until reapportionment

in 2002, was more Republican than Democratic. When the lines were redrawn

by the California Legislature, Representative Tauscher easily won

reelection to a fourth term, with 75 percent of the vote against

Libertarian candidate Sonia E. Harden. In 2004, Representative Tauscher

won reelection with 66 percent of the vote against Republican Jeff

Ketelson, and in 2006 and 2008 voters returned her to office with 66

percent and 65 percent of the vote, respectively. On May 5, 2009,

Representative Tauscher was nominated by President Barack Obama to be the

Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security. On

June 25, 2009, Representative Tauscher was confirmed to the position of

Under Secretary of State by a voice vote of the United States Senate and

resigned her seat in Congress the next day to take the position.

Representative Tauscher represented the United States at numerous

international meetings and negotiations, including setting into motion the

New START Treaty, the first major nuclear arms reduction and limitation

agreement with Russia in over two decades, which was signed in 2009, and

ratified in 2010. Representative Tauscher served the Obama administration

as Under Secretary of State until February 7, 2012, when she was named

Special Envoy for Strategic Stability and Missile Defense, a position she

held until August 31, 2012. In 2013, Representative Tauscher was elected

chairperson of the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, a group of 28

global retailers, and led efforts that created industry safety standards

in response to the fire and collapse of a Bangladeshi garment factory that

killed over 1,000 workers. In March 2013, Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr.,

appointed Representative Tauscher as the chair of the Governor’s

Military Council and was tasked with expanding defense industry jobs and

investment in California. On September 17, 2013, Representative Tauscher

was named as an independent member of the Board of Governors for Lawrence

Livermore National Laboratory and Los Alamos National Laboratory, and

served as chair of the Board of Governors beginning on February 16, 2018.

On June 2, 2017, Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr., appointed Representative

Tauscher to serve on the Board of Regents of the University of California.

She passed away in 2019. Named by Senate Concurrent Resolution 77, Res.

Chapter 32, 09/11/20.

(Image source: Find a Grave)

Interstate Submissions

Interstate SubmissionsThe portion from Route 13 to Walnut Creek was submitted for inclusion in the interstate system in 1945; it was not accepted.

Scenic Route

Scenic Route[SHC 263.3] From the Alameda-Contra Costa county line to Route 680 in Walnut Creek.

Classified Landcaped Freeway

Classified Landcaped FreewayThe following segments are designated as Classified Landscaped Freeway:

| County | Route | Starting PM | Ending PM |

| Alameda | 24 | R1.85 | R4.88 |

| Alameda | 24 | R5.24 | R5.89 |

| Contra Costa | 24 | R0.40 | R0.62 |

| Contra Costa | 24 | R1.82 | R2.85 |

| Contra Costa | 24 | R3.29 | R5.26 |

| Contra Costa | 24 | R5.53 | R9.14 |

From Route 680 in Walnut Creek to Route 4 near Pittsburg.

Post 1964 Signage History

Post 1964 Signage History

In 1963, this segment was defined as "Route 680

in Walnut Creek to Route 4 near Pittsburg." In 1981, Chapter 292 changed

the wording to "near Walnut Creek", but it was changed back to "in Walnut

Creek" by Chapter 1187 in 1990.

In 1963, this segment was defined as "Route 680

in Walnut Creek to Route 4 near Pittsburg." In 1981, Chapter 292 changed

the wording to "near Walnut Creek", but it was changed back to "in Walnut

Creek" by Chapter 1187 in 1990.

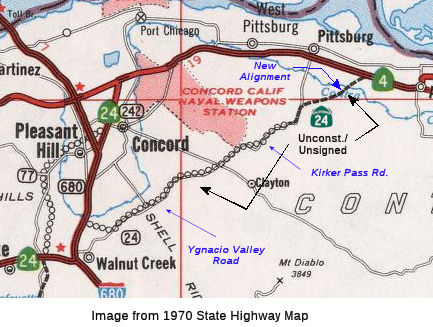

Planning maps have shown a routing that follows Willow Pass road from Walnut Creek to just outside of Antioch. Until 1991, Route 242 between Concord and Route 4 was signed as Route 24, but field reports indicate this is no longer the case. There is one map that shows Route 24 continuing northeast of Route 4 to Collinsville and then towards Route 160

In Concord, the freeway routing was constructed by 1992; that routing was transferred to Route 242. The traversable routing that corresponds to the proposed bypass is Ygnacio Valley Road and Kirker Pass Road. The traversable routing was considered adequate in 1972, but local agencies have discouraged state adoption. The freeway route adoption was rescinded effective 4/16/1975.

The 2013 Traversable Routing report notes that the segment from Route 680

to Route 4 corresponds to Ygnacio Valley Road and Kirker Pass

Road. Considered adequate in 1972, but local agencies have discouraged

state adoption. Freeway route adoption (4.5 miles) was rescinded 4-

16-75. No recommendation.

Pre 1964 Signage History

Pre 1964 Signage HistoryThis new routing is LRN 256, added to the state highway system in 1959. Present-day Route 242 was signed as Route 24 prior to 1992.

Status

StatusIn June 2011, it was reported that the Walnut Creek City Council had a number of plans for Ygnacio Valley Road, including in-pavement lights at various locations, $550,000; Ygnacio Valley Road sidewalk, Oakland Boulevard to Parkside Drive, $750,000; speed display signs along Ygnacio Valley, $130,000; left turn extension lanes at Ygnacio Valley and San Carlos Drive, $500,000; southbound left turn extension lane at Civic Drive and Ygnacio Valley, $600,000; eastbound left turn extension at Ygnacio Valley and Marchbanks Drive, $300,000; westbound left turn extension on Ygnacio Valley at Walnut Boulevard, $400,000; and a westbound left turn extension on Ygnacio Valley at Homestead Avenue, $350,000.

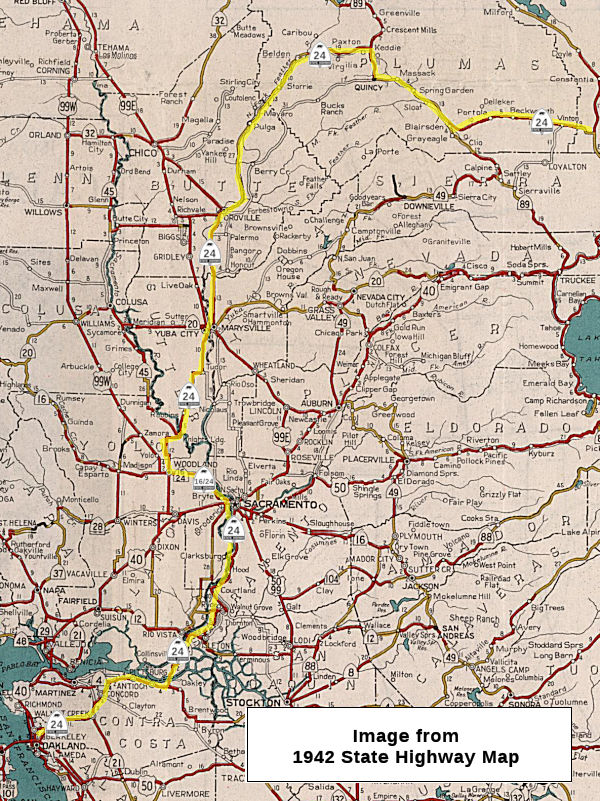

Prior to 1964, Route 24 continued from Pittsburgh to a junction with US 395 near Hallelujah Junction via Oroville and Quincy.

Post 1964 Signage History

Post 1964 Signage HistoryThe 1964 renumbering reallocation the segments E of Pittsburgh to Route 4 (Concord to Antioch), Route 160 (Antioch to Sacramento), Route 16 (Sacramento to Woodland), Route 113 (Woodland to Yuba City/Marysville), and Route 70.

Pre 1964 Signage History

Pre 1964 Signage History

In 1934, Route 24 was signed along the route from

Woodland at Jct. US 99 to Jct. Route 7 (now US 395) near Reno Junction,

via Oroville and Quincy (Reno Junction was likely the former name of what

is now Hallelujah Junction, Reno Junction having replaced Chats). It

appears it was extended, perhaps in 1936, to eventually have the route

from US 40 in Oakland to US 395 near Reno Junction.

In 1934, Route 24 was signed along the route from

Woodland at Jct. US 99 to Jct. Route 7 (now US 395) near Reno Junction,

via Oroville and Quincy (Reno Junction was likely the former name of what

is now Hallelujah Junction, Reno Junction having replaced Chats). It

appears it was extended, perhaps in 1936, to eventually have the route

from US 40 in Oakland to US 395 near Reno Junction.

Route 24 started at US 40 (now I-80) at the Oakland City Hall at 14th and

San Pablo. It then ran along Broadway to College, then along College to

Claremont Ave. Along Claremont, it entered Berkeley. It jogged briefly

along Ashby Avenue (present-day Route 13, LRN 206, defined in 1935) to

Tunnel Road, continuing into Contra Costa County. The route was LRN 75.

(Source: Old Oakland Maps, 1936)

Route 24 then ran E to Walnut Creek (along present-day Route 24); this was LRN 75. It was then likely cosigned with Route 21 until the Route 21/Route 24 junction (this segment of Route 21 was also LRN 75). This was all defined in the 1931-1933 time, but was not signed as Route 24 in 1934.

From Route 4 (Route 24's present-day terminus), it continued cosigned with Route 4 between from near Concord to near Antioch (this was LRN 75, defined in 1931).

Route 24 then ran N to Sacramento, following the route of present-day Route 160, entering along Freeport Blvd. This was LRN 11, defined in 1933. It originally ran N on Freeport to Broadway.

In Sacramento, Route 24 ran W along Broadway as part of LRN 50. It

then ran N along 3rd/5th St., also as part of LRN 50 (Route 16, defined in

1933). It continued N to "I" street, co-signed with Route 16.

In Sacramento, Route 24 ran W along Broadway as part of LRN 50. It

then ran N along 3rd/5th St., also as part of LRN 50 (Route 16, defined in

1933). It continued N to "I" street, co-signed with Route 16.

Prior to 1960, Route 24 continued W out of the city co-signed with Route 16 along LRN 50 to Woodland.

In Woodland, Route 24 diverged from Route 16 and continued N to Yuba City/Marysville along LRN 87. It was cosigned with US 40A, and this segment is now part of Route 113.

In 1954, Sign Route 24 was either co-signed or resigned as Alt US 40

(US 40A). The article announcing the designation indicated that existing

signs would be replaced by US 40 signs with the designation "Alt". The

article indicated that for the first 10 miles N, from US 40 in Solano

County, the new alternate route would be designated as US 99W and US 40A.

A new section of highway was being constructed to intersect with the

existing US 99W at the Woodland Wye. This would be the segment that is now

Route 113. In Woodland, US40A joined with the existing US 99W / Sign Route 24 to Yuba City; this is now Route 113. US 40A then followed Sign Route 24

(now Route 70) through Oroville and Quincy to US 395. Lastly, US 40A

followed US 395 S to Reno, which was the eastern terminus of US 40A. The

goal here was to provide an alternate route across the Sierras when Donner

Pass was closed.

In 1954, Sign Route 24 was either co-signed or resigned as Alt US 40

(US 40A). The article announcing the designation indicated that existing

signs would be replaced by US 40 signs with the designation "Alt". The

article indicated that for the first 10 miles N, from US 40 in Solano

County, the new alternate route would be designated as US 99W and US 40A.

A new section of highway was being constructed to intersect with the

existing US 99W at the Woodland Wye. This would be the segment that is now

Route 113. In Woodland, US40A joined with the existing US 99W / Sign Route 24 to Yuba City; this is now Route 113. US 40A then followed Sign Route 24

(now Route 70) through Oroville and Quincy to US 395. Lastly, US 40A

followed US 395 S to Reno, which was the eastern terminus of US 40A. The

goal here was to provide an alternate route across the Sierras when Donner

Pass was closed.

(Source: Roseville Press-Tribune 3/23/1954 via Joel Windmiller

(email), 11/12/2023)

Around 1960 the routing changed to a new routing along LRN 232, which used Jiboom Street and El Centro Street. This routing used the original Jiboom Street bridge over the American River and Main Drainage Canal. The Gribblenation Blog, "Highways in and around Old Sacramento; US 40, US 99W, CA 16, CA 24, CA 70, CA 99, CA 275, and more" provides a detailed history of the various highways (US 40, US 99, Route 16, Route 24, Route 70, Route 99, Route 275, Route 51, I-5, and I-80 in the Old Sac area.

In October 2018, it was reported that the City

of Sacramento and Caltrans have initiated a project that will replace the

historic I-Street Bridge (for vehicular traffic) and the Jibboom Street

approach to the bridge for a new vehicular continuation of Railyards Blvd.

to C Street. The I Street Bridge is 100 years old (and is a former routing

of Route 16, Route 24, US 40, and US 99) and the lanes are too narrow to

serve buses, there are no bicycle lanes, and sidewalks are too narrow to

meet accessibility standards. The I Street Bridge and the four associated

approach structures are on the eligible bridge list for federal funds for

replacement and/or rehabilitation through the Highway Bridge Program

(HBP). The I Street Bridge has been classified as functionally obsolete,

and the existing approach structures have been classified as structurally

deficient. The I Street Bridge Replacement project will include

construction of a new bridge upstream of the existing I Street Bridge. The

new bridge will cross the Sacramento River between the Sacramento

Railyards and the West Sacramento Washington planned developments and

provide a new bicycle, pedestrian, and automobile crossing. The existing I

Street Bridge would continue to be used by the railroad. The approach

viaducts to the existing I Street Bridge will be demolished, which should

result in better access to the water front in both cities. (See Route 16

for the new routing)

(Source: City of Sacramento, I-Street Bridge Replacement)

Over on AAroads, Scott Parker (Sparker) noted the following about the I-Street routing: The original LRN 232 (after 1959 signed as Route 24) diverged from LRN 50/Route 16 at the intersection of the I Street extension bridge immediately east of the Sacramento River swing-span (shared with UP/former SP tracks on the lower/ground level deck) and Jiboom Street (both are elevated over the RR tracks). It headed north on Jiboom over a through-truss bridge crossing the American River; the street ended at Garden Highway -- atop the river levee --, at which point LRN 232/Route 24 turned west. About a mile west of there, the state highway diverged from Garden Highway along a broad arc descending north from the levee onto El Centro Avenue, which it utilized north into Sutter County. LRN 232 and Route 24 terminated at LRN 3/US 99E at a diamond interchange in Olivehurst.

In November 2022, it was reported that the

plan to turn the top level of the I Street Bridge into a pedestrian

walkway and bike lane over the Sacramento River was progressing. In Fall

2022, project planners filed financial documents, and in late October 2022

the project was recommended for a $16 million grant through the

state’s Active Transportation Program. The current bridge will be

superseded by a new bridge between C Street in West Sacramento and the

Railyards — a $260 million, 300-foot-long feat of architecture that

will replace the I Street Bridge as the route cars take over the river. As

for the old bridge, the plan is to use the 111-year-old I Street Bridge

for railroad traffic, which runs on the bottom deck of the bridge. As for

the top? The city of West Sacramento has spearheaded the plan to repair

the bridge’s narrow sidewalk and turn the vehicle lanes into a

bicycle track and walkway. The $16 million state grant still has to be

formally approved by the state Transportation Commission. The Sacramento

Area Council of Governments previously awarded the project $3.6 million to

complete the final design and right-of-way phase. The total cost of

planning and constructing the project is estimated at $22.6 million. After

securing more than $19 million in outside funding, the city will pay the

rest. Final planning should be complete and construction could be ready to

begin in or before 2026 — but that will largely depend on the timing

of the completion of the new Railyards bridge. The plan is to be ready so

that as soon as the new bridge is cleared to start taking vehicle traffic,

the deck conversion of the old bridge can start. The project should be

finished by late 2027 or 2028.

(Source: Sacramento Business News, 11/7/2022)

In December 2023, it was reported that

Construction on a new bridge connecting West Sacramento and the Railyards

is anticipated to begin in 2025. Currently, the I Street Bridge

replacement project is not fully funded, and construction will begin once

all financial support is secured. So far, officials have completed the

environmental documentation, and are working through the permits,

right-of-way acquisition and final design. Even after construction starts

it’ll be a while before the new bridge graces the city. The project

will take approximately four years to construct to comply with

environmental mitigation and flood control work windows. If construction

begins in 2025, the new bridge would be completed by 2029. The existing I

Street Bridge is more than 110 years old; the nine-foot lanes are too

narrow to serve buses, there are no bicycle lanes, and the sidewalks are

too narrow to meet current accessibility standards. A new bridge will be

built upstream from the current one and will cross the Sacramento River,

connecting the Railyards to West Sacramento’s Washington

neighborhood. The current bridge will remain and serve as a railroad

crossing on the lower deck, the city said, while the upper deck may be

used by pedestrians and bicyclists. The new vertical lift bridge will

feature 6-foot bike lanes and 12-foot shared paths for pedestrians and

bicyclists. It can also withstand more than 25,000 vehicles daily,

according to the city’s 2020 news release. The bridge’s

contemporary blueprint is bolstered by two curved green and white pillars

on each side, which light up at night.

(Source: Sacramento Bee, 12/15/2023)

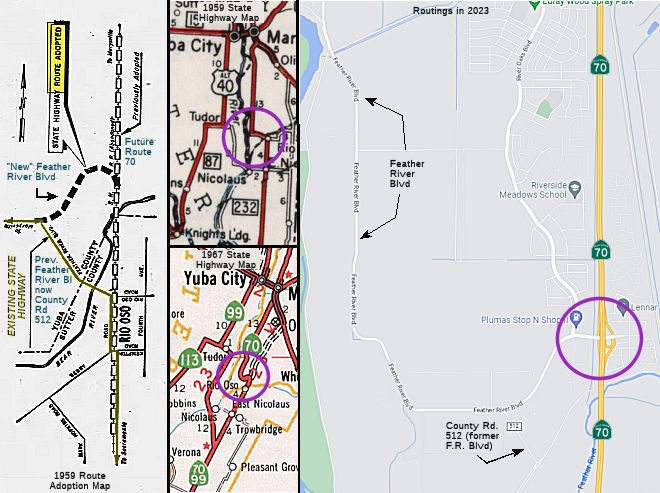

In 1959, the CHC adopted a routing for a connection between the "future Route 232 (LRN 232) freeway"

(today's Route 70 freeway routing) and the existing Route 232 highways

(Feather River Blvd) near Rio Oso. This connector swings W from the

adopted freeway route to join Feather River Blvd about a mile to the west.

It is hard to see today, because although Feather River Blvd was "new"

Route 24 (and later Route 70) at the time, it has since been relinquished

by the state and downgraded to a county road. The plans called for the

building of a two-lane bridge over the Bear River, upstream from the

existing bridge. This is part of the first stage of construction of the

new Route 70 freeway. The article indicated that when the LRN 232 freeway

(today's Route 70) was extended to US 99E (Route 99) in Marysville, this

connection would be incorporated into the Bear River interchange, and used

as a county road connection (as LRN 232 would move off Feather River

Blvd). However, in 1959, Feather River Blvd was new Route 24 headed north

on El Centro Road from the Sacramento River. Old Route 24 resigned the Alt

US 40 1955-64 alignment (current 113) from Woodland, which headed north at

Tudor at the current junction of Route 99 and Route 113 then headed north

into Yuba City. In this area for a small period of time (i.e., from 1964

until I-5 was completed and US 99 signs came down), California had both US 99 and California Route 99, but not on the same stretch of highway.

In 1959, the CHC adopted a routing for a connection between the "future Route 232 (LRN 232) freeway"

(today's Route 70 freeway routing) and the existing Route 232 highways

(Feather River Blvd) near Rio Oso. This connector swings W from the

adopted freeway route to join Feather River Blvd about a mile to the west.

It is hard to see today, because although Feather River Blvd was "new"

Route 24 (and later Route 70) at the time, it has since been relinquished

by the state and downgraded to a county road. The plans called for the

building of a two-lane bridge over the Bear River, upstream from the

existing bridge. This is part of the first stage of construction of the

new Route 70 freeway. The article indicated that when the LRN 232 freeway

(today's Route 70) was extended to US 99E (Route 99) in Marysville, this

connection would be incorporated into the Bear River interchange, and used

as a county road connection (as LRN 232 would move off Feather River

Blvd). However, in 1959, Feather River Blvd was new Route 24 headed north

on El Centro Road from the Sacramento River. Old Route 24 resigned the Alt

US 40 1955-64 alignment (current 113) from Woodland, which headed north at

Tudor at the current junction of Route 99 and Route 113 then headed north

into Yuba City. In this area for a small period of time (i.e., from 1964

until I-5 was completed and US 99 signs came down), California had both US 99 and California Route 99, but not on the same stretch of highway.

(Source: 1959 news clipping via Joel Windmiller, 1/27/2023)

From Marysville, Route 24 ran through Oroville continuing through

to Belden (this was LRN 87 (defined in 1933) between Robbins and Oroville,

and LRN 21 (defined in 1909) to Belden, and is present-day Route 70), and

then E through Twain, Quincy (running concurrant with Route 89) to Mohawk

(this was LRN 21), and then by its lonesome to US 395 near Long Creek

(also LRN 21).

From Marysville, Route 24 ran through Oroville continuing through

to Belden (this was LRN 87 (defined in 1933) between Robbins and Oroville,

and LRN 21 (defined in 1909) to Belden, and is present-day Route 70), and

then E through Twain, Quincy (running concurrant with Route 89) to Mohawk

(this was LRN 21), and then by its lonesome to US 395 near Long Creek

(also LRN 21).

The portion from near Cherokee and Quincy was under construction, and so a Temporary Route 24 ran from Oroville to Quincy through Berry Creek and Merrimac and Bucks (likely a temporary routing of LRN 21, 1934-1935, perhaps today's Route 162). The Feather River routing was used between 1935 and 1953. Later, a portion of Route 24 was redesignated as Alternate US-40 [1953-1964; for a while, cosigned as Route 24/US 40A] (and is present day Route 70), and Route 24 was truncated to the present day route of Route 99 and Route 113 and Woodland (pre-1964 LRN 87). Route 24, cosigned with Route 16, ran from Woodland to Sacramento. Later, that portion was taken from Route 24, becoming part of I-5.

According to Chris Sampang and Joel Windmiller, the following are some former routings of US 40A/Route 24 between Woodland and Reno:

Chris also notes that Scott Road north of Reno Junction to just south of Omira was also US 395 pre-expressway. Constantia Road between Omira and Doyle, Doyle Loop in Doyle itself, and Old Highway from Doyle to just west of Lassen County Route A26 also appear to be former alignment (Old Highway passes south of the Doyle State Wildlife Area, but the current US 395 expressway goes right through it between Laver Crossing and Lassen County Sign Route A26.)

National Trails

National Trails

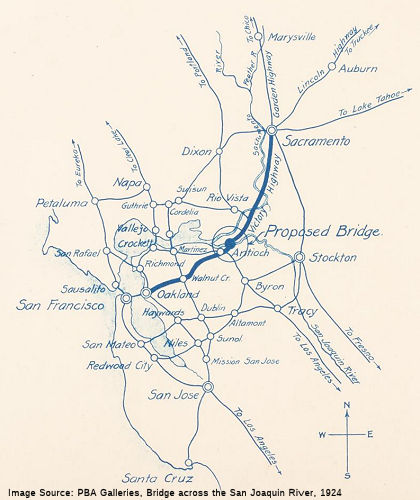

This route was selected by the Victory Highway Association as part of its route from Sacramento to

San Francisco by the 1926 opening of the Antioch-Sherman Bridge, in spite

of the twelve miles of poor road S of Rio Vista and the two ferries

existing at Three-Mile Slough and at Antioch-Sherman.

This route was selected by the Victory Highway Association as part of its route from Sacramento to

San Francisco by the 1926 opening of the Antioch-Sherman Bridge, in spite